The First World Cup

Martin Chandler |

One Day International cricket began in Australia on 5 January 1971 by accident. The third Test of that season’s Ashes series had been due to begin at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on New Year’s Eve, but rain prevented play starting and the decision was made that, rather than have a meaningless day’s cricket on the scheduled final day, the two teams would play a match limited to 40 eight ball overs per side.

The game itself was not particularly memorable. England were all out for 190 with two balls of their allocation left, a total which Australia comfortably overhauled with five overs and five wickets to spare. What was more interesting was that more than 46,000 people attended the match, and it was not lost on the administrators that the proportion of those spectators who were women and children was very much greater than it might have been for a day’s Test cricket.

There were mixed reactions to the experiment. A local supporter was quoted as saying “Terrific. If they played cricket all the time like this, they’d pack the MCG. No risk. you can’t tell me there’s any less skill involved. I’d reckon there’s more skill”. Such comments were nothing short of blasphemy to some traditionalists, particularly Australians who, at that stage, had virtually no experience of this sort of cricket. The reaction of the veteran English journalist, EW “Jim” Swanton, a long time critic of limited overs cricket was, however, more measured. “There is clearly a great future for this sort of thing”. He was not alone in facing up to the inevitable.

The 1972 edition of Wisden, surprisingly in many ways, all but ignored this development in the game. The fact of and the explanation for the match being played was included in the tour’s section in the almanack but the game itself was treated as a minor match and only the briefest details given – there was no scorecard and, most oddly, no mention of the game in the influential and respected Notes by the Editor section, notwithstanding that those notes did dwell on the issue of limited overs cricket generally at some length.

In its 1973 edition the almanack briefly referred to the July 1972 meeting of the ICC when it was decided that a World Cup, using the limited overs format, should take place as soon as possible. This was despite the fact that, at the time of the meeting, no further ODI’s had been played. Following the decision, and after the five Test Ashes series, England did defeat Australia 2-1 in a series of three ODI’s, sponsored by insurers Prudential. This time the matches were fully recorded in Wisden, although the concept of the ODI was mentioned only in passing by Editor Norman Preston, and in respect of the seemingly momentous decision to hold a World Cup he chose not to comment at all.

The July 1973 meeting of the ICC brought confirmation of a World Cup to be played in England in 1975. By now there had been seven ODI’s played in total, although India and West Indies had yet to play even one. That said there seems to have been no misgivings about the decision. Once again Wisden faithfully recorded the outcome of the meeting, and pursued its policy of fully recording those few ODI’s that were played, but inexplicably Preston again felt the subject of a World Cup of insufficient import to mention it in his editorial notes in the 1974 edition.

The following year, 1975, the year of the cup itself, brought no more than a passing comment from the editor that, after the disastrous showing against Lillee and Thomson the previous winter, England needed to find some new talent to deal with the World Cup and the return series that followed it. It is tempting to conclude that Preston did not approve, although in the 1976 edition, by which time the Cup could clearly not be ignored, he did comment positively about the tournament and its impact on the game – it nonetheless remains a source of diappointment, as well as surprise, that he did not articulate his views on the subject earlier.

The format for the Prudential Cup, as the sponsors understandably wished it to be called, was a simple one. There were eight teams that were split into two groups of four. The two favourites were England and Australia. England seemed to have the most straightforward task as they were joined by India, New Zealand and East Africa (a side drawn from Zambia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania). Australia’s first round opponents were West Indies and Pakistan together with a Sri Lankan side that was still five years away from gaining Test status. The desires of the sponsors apart there was another compelling reason not to call the tournament the World Cup that being the obvious one that the best team in the world weren’t present. With batsman of the quality of Barry Richards and Graeme Pollock, all rounders like Eddie Barlow, Mike Procter and Clive Rice, not to mention that most perfect combination of parsimony and penetration, Vintcent Van Der Bijl, it is difficult to envisage anything other than a South African triumph had they been allowed to compete. There were another 17 years to elapse before the competition could claim to be a truly World competiton, but it is the first ever tournament where the South Africans were most missed.

There were to be three group games for each country. The top two in each group would then compete in two semi finals followed by the final. Fifteen games altogether and the competition to be concluded within a fortnight. As the tournament was played in June the maximum amount of daylight was available so it was 60 six ball overs per side, with bowlers limited to twelve overs each – that and a stricter attitude to wides apart, the game was a normal game of cricket, played in whites, without fielding or other artificial restrictions.

By the time the teams lined up there had been eighteen ODI’s altogether. England had played in fifteen of those, Australia and New Zealand seven each, Pakistan three and West Indies and India just two. Experience of the conditions and the format largely accounted for the expectation that England were most likely to succeed. India were on their way down after the heights they had touched in the early part of the decade and were the least experienced as few of their players plied their trade in England. West Indies were not yet the team they would be in a few years time. That said almost all of the West Indies’ key players were contracted to English counties. The Pakistanis, with their exciting batting lineup, all of whom bar Wasim Raja had also honed their skills playing county cricket, were considered a good prospect as well. New Zealand, although overly dependent on Glenn Turner finding his best form, were also expected to provide a stern test. As for Australia they were always going to be hard to beat, but there was a general feeling that they were not particularly keen on the one day game, and despite having had a domestic competition for a few years only Greg Chappell had any experience of county cricket and it was felt that, as long as Lillee and Thomson could be held at bay during their 24 overs, the Aussies did not have quite enough to succeed. Richie Benaud, in summing up the prospects of the competing nations prior to the tournament, said of his countrymen, ” they regard limited overs cricket as not as important as Test cricket…”. No one paid much notice to the two outsiders.

The eight team format allowed the group matches to be played in three tranches with all eight countries in action at the same time. The tournament was blessed with fine weather throughout and although three days were set aside for each match the reserve days were not required. The first four matches were played on 7 June. New Zealand and West Indies brushed aside East Africa and Sri Lanka and the interest therefore lay in a bizarre match between England and India at Lord’s and the contest between Australia and Pakistan at Headingley.

The Lord’s match was not one where the sport covered itself in glory, due primarily to the antics of the Indian batsmen in general and their star man, Sunil Gavaskar, in particular. England won the toss and elected to bat. Indian captain and off spinner Srinivas Venkataraghavan bowled tidily but the rest of the attack, shorn of its great spinners (Erapelli Prasanna and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar were not even in the party and Bishen Bedi was omitted for the game) was no test for the experienced England batsmen, and the medium pace of Madan Lal, Syed Abid Ali, Mohinder Amarnath and Karsan Ghavri went at well over five an over as England totalled 334 for 4 in their 60 overs. The main contributor, with 137, was Dennis Amiss. In reply India could muster only 132 to lose by 202 runs. The remarkable feature of the innings was that, like England before them, India lost only four wickets. Gavaskar, opening as usual, sat on his splice throughout the 60 overs for just 36 runs. His opening parter, Eknath Solkar, showed no more urgency and even Viswanath, who struck five boundaries as he top scored with 37, had a scoring rate of barely 60 runs per 100 balls.

There were more than 16,000 spectators at Lord’s, many of them Indian, and they were beside themselves with anger and disappointment at the resolute refusal of their batsmen to even attempt to force the pace. There were several instances of fans running on to the pitch but nothing could persuade India to try and accelerate. The one man who would have been guaranteed to give the innings some impetus, Farokh Engineer, never even got to the crease. The Indian management subsequently condemned the batsmen’s actions but, perhaps surprisingly given the content of the Team Manager’s press release, no disciplinary action was taken against anyone; “This is not the way Gavaskar should have played it, and I do not personally agreee with his tactics. But he felt that against such a big England total he would get in some batting practice on a good wicket against a good attack”. There were suggestions that Gavaskar’s actions were some form of protest, either against Venkat being captain, or against Bedi’s omission from the team, or both, but that has never been more than speculation. One thing that future Indian sides have rubbished was another theory that was articulated in certain quarters, that being that Indians were temperamentally unsuited to limited overs cricket. As for Gavaskar himself he gave a most unconvincing explanation in an early volume of autobiography, Sunny Days, which amounted to an unequivcal denial of the suggestion he was, effectively, taking a net, and that he was doing his best but was woefully out of touch. Amusingly he also chose to place part of the blame on England for setting defensive fields notwithstanding their imposing total.

At Headingley there were as many as 21,000 present making the game, effectively, a home fixture for Pakistan. Australia won the toss and batted and made good progress to start with before running into trouble in the middle part of their innings. Their sixth batsman, Ross Edwards, then came in to join Greg Chappell and in partnership with him, and later the tail, he played the sort of innings that in years to come his compatriot Michael Bevan would become famous for. Edwards unbeaten 80 took to Australia to 278, a large total in those days. Pakistan would have been disappointed with some of their batting, although Majid Khan and skipper Asif Iqbal performed well. They were always behind the clock but any lingering hopes of victory were dashed when Dennis Lillee came back for his final spell and bowled Asif before blowing away the tail. In his 12 overs Lillee took 5-34. Former England skipper Tony Lewis wrote of him “His speed and the unerring line he maintains just on or around off stump are going to make him a terribly difficult bowler to face later in the year, and when you watch his legs carry him strongly over a fast rhythmical run-up, black mane flying, the back suddenly arched and the ball projected out of a flying pivot, you wonder just what courage it took to come back to the game having suffered three stress fractures of the spine”.

In the second round of matches India had a comfortable ten wicket win over East Africa. Still not dominating the bowling Gavaskar nevertheless took half as long to score twice as many runs as he had against England. The home side too had a comfortable victory. It was Keith Fletcher this time who recorded a century as his side scored 266 against New Zealand. With Turner out early for just 12, and wickets falling regularly the visitors ended up 80 runs short.

Australia took on Sri Lanka at The Oval and they racked up 328 for 5 in their allocation of 60 overs. With Jeff Thomson sending two of the Sri Lankan batsmen to hospital a hammering might have been expected but, showing the sort of skill and courage that has become synonymous with Sri Lankan batsmen over the years, they managed to get within 52 of the Australian total when their overs ran out. Despite their difficulties with Thomson the Sri Lankans did something Pakistan could not do and drew the sting of Lillee, who was not even called upon to complete his full complement of overs, the ten he did bowl giving him the very ordinary figures of 0-42.

The match of this round of games was at Edgbaston where Pakistan met West Indies. Pakistan, after their demoralising defeat to Australia, would have been even gloomier as a result of losing skipper Asif to a surgical procedure, and a young Imran Khan, who was required by his examiners at Oxford University. Despite those setbacks half centuries from Majid, Mushtaq Mohammad and Wasim Raja took Pakistan to a good score, 266-7. When the West Indies replied Sarfraz took three early wickets and, despite a solid 53 from skipper Clive Lloyd, wickets fell regularly and, at 203-9, it looked all over as Andy Roberts came out to join Deryck Murray. There were just under 15 overs to go and 64 needed. Initially Majid decided to use up his strike bowlers’ overs early to try and take the last wicket. That perfectly reasonable strategy failed and his lesser bowlers had to finish the innings. Amidst great tension the, by contemporary West Indian standards, unusually orthodox Murray, and the tall gangling fast bowler got their side home with just two balls to spare.

For the third round of matches there was not a great deal left to decide. Australia and West Indies were already through from Group B and met at The Oval. Pakistan played Sri Lanka, who could not repeat their heroics against Australia, and won by 192 runs. At The Oval West Indies easily beat Australia by seven wickets. During their pursuit of 193 for victory the diminutive left hander Alvin Kallicharran scored 35 from ten successive deliveries from Lillee, five of them bouncers – the match result was less important than the psychological blow that was struck by such a withering assault on a great bowler.

In Group A England were already through and they were no more troubled by the East Africans than New Zealand and India had been. Those latter two played out the other match for the right to join England in the semi finals and an unbeaten century from Turner saw New Zealand overhaul India’s 230 in the penultimate over. It was a fine innings from a man who deserves to be held in much higher regard today than he is.

The semi finals paired England with Australia and New Zealand with West Indies. In an age where television did not pull quite so many strings both matches were due to be played on Wednesday 18 June, at Headingley and The Oval respectively. The Headingley crowd witnessed what to this day remains one of the more remarkable limited overs matches. There were plenty of clouds around in the morning and both captains chose to go into the match with an all seam attack. Chappell won the toss and had no qualms about inviting England to bat first. Gary Gilmour was a left arm seam bowler who, in helpful conditions such as those encountered at Headingley that day, could move the ball sharply both ways. He opened the bowling with Lillee and by the end of his ninth over had six wickets to his name. He ended up with the incredible figures of 6-14 from his twelve overs. At 37-7 England were down and out and although skipper Mike Denness led a rearguard action that saw the total eventually raised to 93, no one on the ground had any doubt that a target of 94 in sixty overs was going to be one the Australians would manage at a canter.

Overhead conditions were unchanged when Australia began their reply but with all the time in the world they reached 17 without alarm before Surrey’s Geoff Arnold, like Gilmour a man who could swing a cricket ball a long way, trapped Alan Turner leg before. As the nation looked on in disbelief Australia then, in the face of hostile and accurate bowling from Chris Old and John Snow, subsided to 39-6, and suddenly 94 looked a distant target. Doug Walters was the not out batsman as Gilmour, his skills wielding the willow now needed, came in at number eight. Walters was a fine batsman but had a poor record in England where he averaged just 25 in Tests against an overall 48. He struggled against the seaming ball and was regularly caught in the gully early in his innings. We England supporters were beside ourselves with anticipation – with a walking wicket at one end accompanied by a man who was surely due a setback the impossible victory seemed within our grasp. Denness immediately moved third slip to second gully, the time honoured means of removing Walters. The New South Welshman had just a single to his name as he proceeded to slice the ball at a comfortable height through the now vacant third slip area. On such glorious uncertainties do cricket matches turn. Gilmour then produced some lusty blows to top score with 28 and Walters eked out 20 as the Australians regained their composure and wrapped up a memorable victory. It was to be nearly 30 years later that another Australian, Andy Bichel, who like Gilmour never performed consistently at the highest level, had a similar World Cup experience, again against England.

Events at The Oval were rather less dramatic as the West Indies eased their way into the final. Like Chappell at Headingley Lloyd decided to bowl on winning the toss. He must have had cause to question the wisdom of that decision while Turner and Geoff Howarth put on 90 for the second wicket but that was an isolated highlight for the New Zealanders who were all out for 158. West Indies lost five wickets in reaching their target and, coincidentally, it was the second wicket that again was the crucial stand with Kallicharran and Gordon Greenidge adding 125. The four quick wickets that New Zealand towards the end of the chase came too late to cause Lloyd?s men any alarm.

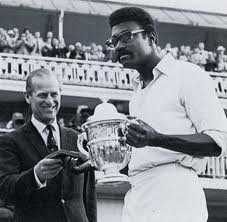

The final took place at Lord’s on Saturday 21st June. The showpiece occasion was watched by a capacity crowd in glorious sunshine. Chappell won the toss and decided to bowl first. There was no cloud cover to help Gilmour and the rest of his all pace attack this time, and it seems likely that Chappell put the West Indies in simply because he reasoned that given the choice Lloyd would, as he had throughout the tournament, have done the same. There was a large and noisy Caribbean contingent in the ground but they were somewhat subdued by the time their captain strode to the wicket when the third wicket fell with just 50 on the board. This was to be a crucial passage of play. Lloyd remains by a comfortable margin the worst starter I have ever seen amongst major batsmen. At the beginning of a Lloyd innings his footwork was always leaden and his timing poor, and it was always a good idea for the faint hearted amongst his supporters to find something else to do for ten minutes. If Lloyd had failed here then disaster would have beckoned for his team but, to the delight of the assembled gathering, it was to be one of his memorable days. He and Kanhai put on 149 for the fourth wicket before, with 102 to Lloyd’s name, Gilmour won a controversial decision from, effectively, the square leg umpire, for a catch at the wicket down the leg side. Lloyd was clearly displeased at the decision and when Gilmour followed that with the wickets of Kanhai and the 23 year old Vivian Richards, to leave the West Indies on 209-6 in the 46th over, a contest that had been accelerating rapidly away from Australia was back on again. When the West Indies innings closed their lower order, and Keith Boyce in particular, had helped raise the total to 291-7.

History records that Australia failed by 17 runs to overhaul the West Indian total but they had only themselves to blame. As many as five Australians were run out. Three of the run out victims were the second, third and fourth wickets to fall. All three were as a consequence of superb throws from Richards, two being direct hits, but had the Australians got their calling right, and obeyed the old mantra never to run on a misfield, then each of those three dismissals could have been avoided. The Australian batting fell away and at 233 the ninth wicket fell. Lillee and Thomson were Australia’s last hope and they made sure that that hope flickered for another 41 runs. With 21 needed from the last two overs Thomson struck the ball in the air to Fredericks at cover. Fredericks took the catch and, having heard the umpire call Vanburn Holder for overstepping, took a shy at the stumps and missed. There was no one backing up the throw. The crowd however did not hear the call and, believing the catch to have ended the game, swarmed over the outfield, gathering up the ball as they ran. Lillee and Thomson stopped and looked blankly at each other before Lillee signalled Thomson to run and the two fast bowlers set out to run all 21 from the same delivery. Sadly for them when the confusion finally abated the umpires called the ball as dead and the Australians were awarded just three runs. Thomson was then dismissed in a manner which summed up the Australian innings. He missed Holder’s delivery completely but, believing Lillee was doing likewise, set off to take a bye to the wicketkeeper. Unfortunately for Australia there was no meeting of minds and Lillee sent Thomson back and despite a spectacular dive to try to regain his ground Murray had the bails off and the game’s first World Cup was on its way to the Caribbean.

The Prudential Cup had been a great success. The fine weather and good cricket had brought the crowds flocking to the grounds and the bean counters were delighted. Sponsors Prudential immediately announced that they would be happy to support the event again and even the players seemed to enjoy it although, reflecting the then prevailing opinion down under, Ian Chappell, when asked after the tournament for his assessment of it, said simply “Enough is enough”. Most of all however it was the new audience that it brought to the game that was the legacy of the first World Cup. Before and after the final pollsters Gallup conducted a survey that established that a massive 57% of men had taken an interest in the tournament. They didn’t bother to ask the ladies – but then it was the 1970s!

Great stuff:)

Comment by archie mac | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2011

Mr F knocks another one out the park

Comment by GeraintIsMyHero | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2011

Great stuff mate.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2011

Wonderful article about a wonderful tournament.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 23 January 2011

Superb Stuff !!!!

Comment by Cevno | 12:00am GMT 23 January 2011

Despite the oneday game being very much in its infancy at the time, this remains one of my favourite world cups. If nothing else, the final was one of the best, with Lloyd’s innings still one of the most brilliant oneday knocks ever imo.

It helped that the weather was fabulous throughout – 1975 was a beautiful English summer. It also helped that in those days the tournament was clogged with a plethora of pointless games against associate sides. The whole thing was done & dusted in a month or so, with a highish proportion of the games being memorable.

SA’s absence didn’t bother me a jot. But I’d only started following the game after their exclusion, so it was just the way things were.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

I agree – it just seemed the natural order of things at the time – particularly as my recollection is that in those days the situation was viewed as intractable so no one talked about a return as it was accepted it couldn’t happen

That said looking back through the old rose tinted spectacles the South African side that never played together looks stronger and stronger the older I get!

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

It is a shame they were removed from the game just when they had the best team in the world.

A clash between the WI and the SA team during circa 1976 would have been worth a look.

Can we not have someone come on and tell us about the reasons why they were not there8-)

I am aware:)

Comment by archie mac | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Great article. Grabbed my attention completely and allowed me to visualize it.

Comment by centurymaker | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Mid-1970s Aus against SA would have been lively too. Especially after the whitewash in 1970.

Perhaps some readers aren’t aware that SA probably wouldn’t have played in the 1975 WC even if they hadn’t been cast into isolation. Anyway …..

Funnily enough, there’s a piece on cricinfo today with Clive Lloyd’s recollections of the 1975 tournament.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Brilliant read Martin.

Kind of reminds me of the first World T20 in 2007. It was new, sort of rushed into a world tournament, looked down on by the purists, not all the teams came up with tactics that suited the new format and the inaugral winners has barely played before.

Comment by Howe_zat | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Although WI hadn’t played many ODIs, all of the WI side had played a lot of county cricket in England, including the three oneday competitions that existed at the time. Aus, otoh, were barely represented in the counties. I have no idea about domestic oneday competitions in those countries though. The other team that did have a lot of their players in the English domestic game was Pakistan.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Cock on article as ever, Mr f. I was surprised to read the Windies weren’t the red hot favs I’d imagined them to be. When I came of cricketing age (early-mid 80s) their dominance was such I just assumed the Caribbean machine was always expected to roll the oppo aside as a matter of course and that the first two WCs were a reflection of their prowess.

I remember being very excited when we (little England) beat them not once but twice in the group stages of the 87 tournament.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011

Mr F with a fantastic read – who’d have thunk it? Another blinder Fred. 🙂

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am GMT 24 January 2011