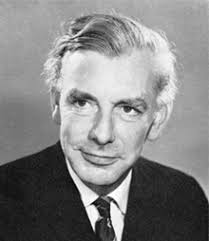

Alan Gibson

Martin Chandler |

I started watching televised Test cricket in the late 1960s and, BBC2 having just been launched, I could watch it all day if I wanted to. I enjoyed the commentary. The men I recall most vividly were Jim Laker and Richie Benaud. They generally took it in turns, but anchor Peter West was involved as well, and I certainly recall Ted Dexter and Denis Compton acting as summarisers.

An issue arose however when my father got home from work, usually around 5.30 pm, or a bit earlier if he could get away, which gave him the last hour or so’s play. It wasn’t so much that I objected to the principle of his turning the sound down on the television and listening to the radio commentary instead, but the fuss he made in setting it up and ‘evicting’ me from ‘his’ armchair caused a completely unnecessary disruption to my viewing pleasure.

After 1975 this ‘ritual’ became much less frequent and soon stopped altogether. The reason it ended was my father’s realisation that the man he considered the doyen of cricket commentators, Alan Gibson, wouldn’t be returning to the airwaves.

Sadly for me I think that at that point I was a bit too young, and probably insufficiently educated, to fully appreciate Gibson. I couldn’t always understand why my father chortled as he did when Gibson was on air or why, occasionally, he used to talk about abandoning his lifelong loyalty to the Daily Telegraph and starting to buy The Times instead, just so he could read Gibson’s prose.

Although I don’t suppose my father did I soon forgot about Alan Gibson and it wasn’t until just over ten years ago, when a book about him written by his eldest son, Of Didcot and The Demon, dropped through my letter box that I finally realised what it was that had captured my father’s imagination all those years ago. I will say now that having reread sections of that book, and others by Gibson Senior for the purposes of writing this post, the rating I gave Of Dicot and the Demon, a mere 4.5 stars, was insufficient to properly reflect its brilliance.

Turning now to my subject today Alan Gibson was born in Sheffield in 1923, his father a Baptist minister. In time the family moved to the West Country, that delightful part of England that Gibson became a part of. He was clearly a highly intelligent man, and in time he graduated from Oxford University with a first class honours degree in history.

The need to complete his National Service part way through his degree meant that it was 1948 before Gibson was seeking employment and, an initial job as a lecturer at the University of Exeter presumably not enthusing him, he soon applied to the BBC for a role in broadcasting.

Something of a polymath Gibson was nonetheless a great cricket enthusiast and, unlike one or two of his peers, he seems to have been a competent cricketer albeit not one whose talents were such that he ever aspired to a level beyond the club game.

Amongst Gibson’s various duties at the BBC was covering cricket commentaries, primarily in Hampshire, Somerset and Gloucestershire. In 1955 he decided to go freelance and, eventually, in 1962 he received the longed for invitation to join the BBC Radio Test Match Special team.

As far as writing is concerned Gibson wrote a good deal, on a wide variety of subjects and, in 1965, a cricket book. Jackson’s Year was an account of the 1905 Ashes series that was won by England 2-0. Skipper Stanley Jackson, for whom that Edwardian summer was to all intents and purposes the end of his First Class career, topped both the batting and bowling averages.

The book had a generally good reception. In Wisden John Arlott welcomed the appearance, sixty years after the event, of a book on a series he described as historic, adding here its story is recounted by a man with a sense of general as well as particular history and the ability to write mature prose. In The Cricketer GD Martineau wrote a rather strange review, which seems largely to be an expression of disappointment that the book was not a biography of Jackson.

Jackson’s Year was also reviewed by Leslie Gutteridge for Playfair Cricket Monthly, and he at least seemed to appreciate that the book was primarily an account of a Test series. In his Cricket Quarterly Rowland Bowen was rather more Martineau than Gutteridge, thundering this book has fallen between two stools: it is not scholarly, nor long enough. Clearly antagonised in some ways by what he had read Bowen did however add that Gibson shows evident judgment ability and some literary ability.

At this point I will concentrate briefly on Gibson the broadcaster who, as indicated, I regret to say I can barely remember. I know though that my late father would certainly agree with some of the testimonials I have found to Gibson the commentator. The view of fellow TMS team member Christopher Martin-Jenkins was: as a broadcaster he had a mellifluous voice and an easy command of language and a twinkling sense of humour. Former Wisden editor Matthew Engel wrote that Gibson as a commentator was close to genius.

The magisterial EW ‘Jim’ Swanton felt sufficiently moved to write to The Cricketer after Gibson’s death that of all the cricket commentators of my time none was easier to work with. He was a pro to his fingertips. Gibson’s Wisden obituary described him as a natural broadcaster with a honeyed voice, a wonderful sense of cadence, a turn of phrase and an eye for the telling detail. As an example of one lasting moment of inspiration if Martin-Jenkin’s memory is correct, and it must be conceded that he himself was not certain of this, then it was Gibson who first described the name of New Zealand pace bowler Bob Cunis as neither one thing nor the other.

There are few of us who get to enjoy an entirely straightforward life, and geniuses never do, and Gibson was no exception. He struggled with alcohol addiction and that cost him his position with TMS when, with growing anger, his boss at the BBC, the former Welsh Rugby Union international Cliff Morgan, listened to his somewhat inebriated thoughts on the final session of the Headingley Test in 1975. Had Gibson been the BBC’s employee and disciplined, it might have been fairer. As it was as a freelancer the BBC simply never booked him again, and nothing was said. He was left with his writing, primarily but by no means exclusively for The Times and The Cricketer

Either because of and/or as a result of his fondness for alcohol there were also mental health issues and, in 1963, there was a suicide attempt and a lengthy admission to a psychiatric hospital. Thirteen years after that, and a year after the TMS ‘sacking’ a second book, A Mingled Yarn, appeared. In the book, and unusually for the time, Gibson laid bare his demons and as a result the book received great acclaim although, it should be noted, eldest son Anthony’s verdict in Of Didcot and the Demon, was that the book had been written movingly, if not entirely honestly.

Married twice both the Gibson marriages ended in divorce, the personal issues doubtless standing centre stage in both of those dramas. Clearly a man with a temper, I have variously read that he could be acerbic, testy and scathing. He seems to have had no time for fools, and was easily bored, another observation of Martin-Jenkins being that: like many with a touch of genius Alan always had a slightly rebellious streak in him and a healthy contempt for those of lesser intellect who might be laying down how he should approach his job.

During the sad year in which he lost his slot with TMS Gibson was paid a great compliment when he was invited to read a tribute to Sir Neville Cardus at the memorial service for Cardus that was held in St Paul’s Church in Covent Garden (known affectionately as ‘The Actors’ Church). Gibson rose splendidly to the occasion. Two sections of the tribute appeal to me particularly, one of which I will come on to, but the other splendidly illustrates the point made by CMJ and quoted in the preceding paragraph as Gibson said of Cardus: the words lyrical and rhapsodical were sometimes applied to him, usually by people who would not know a lyric from a rhapsody.

Financial pressures were ever present for a man with four children from two families, and there must have times when he regretted not seeking out a more lucrative career than the one he chose. There was a telling observation from Ivo Tennant in his obituary for Gibson in The Cricketer when he wrote: in a sense, Gibson was too clever for his own good. Broadcasting and journalism did not fulfil his first class mind. Nonetheless the overriding impression of Gibson is a positive one.

Gibson’s third book appeared in 1979. He had been working on The Cricket Captains of England for years, and the long disappearance of The Times from the newsstands, caused by the bitter print workers’ dispute of 1978, gave him the time to finish it. If, after Jackson’s Year, there were any doubt as to his ability to write a serious cricket book, then this one erased it. Swanton wrote Mr. Gibson has set himself to fill a broad canvas, and he has succeeded to a degree that I doubt whether any other contemporary cricket writer could have approached. It was a serious piece of research and writing, but the sense of humour could not be kept completely under control. Gibson ended his preface with; I have never been much of a man for sums, and I am sure I will have made many statistical errors. I shall be deeply grateful to any reader who does not point them out to me.

Five years after The Cricket Captains of England was published The Times, as the BBC had before them, tired of the restrictions that Gibson’s drinking put on his ability to fulfil his obligations to them and another contract was gone, and the second marriage went as well. Gibson continued to do some writing and, two years later his last book appeared, Growing up with Cricket. This was another project that Gibson had been working on for some considerable time and was effectively a second autobiography, this time dealing with the cricketing issues that A Mingled Yarn had largely left alone.

Alan Gibson seems never to have stopped drinking and he died in a Taunton nursing home in 1997 at the age of 74. It had been a sad deterioration and he had done little writing in his later years, and that which he had done generally lacked the old magic. In 1992 West Country journalist Richard Walsh published an essay of Gibson’s on the subject of Jack Davey, a stalwart left arm fast medium bowler from Gloucestershire. It was not Gibson’s best work. A similar effort on the subject of Dennis Silk appeared the following year and was better, but jointly credited to Walsh who, one is left to suspect, was very much the main writer. Amongst the decline there was however one piece in which Gibson arrested the decline when he was asked, in 1992, to contribute a memoir to The Cricketer following the death of his old friend Arlott.

Another fine writer/journalist from the West of England who knew Gibson well was David Foot, who described him as the academic who got lost on his way to the cricket ground. The ground in question was generally a county ground rather than one hosting an international – Swanton expressed the view of many when he observed that Gibson’s wit and humanity were better attuned to county cricket.

The dust jacket of A Mingled Yarn contains a testimonial from Arlott, describing Gibson as quite the most amusing sports reporter writing at the present time. His writing represented anything but straight reportage. In Foot’s words, Gibson might, occasionally, tell readers who had won the toss, but then he was off, in a discursive and peripheral account of his daily thoughts. Long time colleague at The Times and, nominally, Gibson’s senior was John Woodcock, who put the same point another way, while I wrote about the cricket, Alan was usually elsewhere writing about a day at the cricket.

I must, of course, provide an example of Gibson’s writing which, limiting myself to one, is a difficult choice. When Gibson gave his eulogy for Cardus he, not unnaturally, made reference to Emmott Robinson, the Yorkshire all-rounder of whom it has often been said that he was, to all intents and purposes, a creation of Cardus. Gibson was rather more prolific in his portrayals, but the principle was the same, an affectionate exaggeration of the characteristics of the individual concerned.

Two of Gibson’s more famous portrayals were of Brian Close (‘The Old Bald Blighter’) and Robin Jackman (‘The Shoreditch Sparrow’) but, for my one example I have, after much consideration, chosen the Somerset seamer Colin Dredge. An honest journeyman rather than a budding superstar Dredge spent a decade in the Somerset first eleven taking almost 450 First Class wickets at a tick over thirty runs each. To Gibson Dredge was ‘The Demon of Frome’, and at the end of May of 1978 after Dredge’s bowling in the Kent second innings had taken Somerset to victory he wrote:-

The Demon of Frome bowled long, painstakingly, and successfully. I have never seen him bowl better. He has, whether consciously or not, adjusted his action since I first saw him: although still prone to no-balls, he has cut out the shuffles and strides out well. His action reminds me very much of that of the present rural Dean of Northleach, whom I saw take many wickets on grounds around Taunton, including this one, and whose action was always regarded as model – just as his sermons still are.

Martin – As a fellow-admirer I enjoyed your piece on Alan Gibson. But there is no mystery about the famous but often misattributed Cunis quote. It was Alan Ross, The Observer 17.8.69

Best, Matthew

Comment by Matthew Engel | 6:04pm BST 7 June 2020