A Philosophical Sidelight on Peter Wynne-Thomas’ book, Cricket’s Historians: PART 2

Devine McKenzie |

| Part I concluded there remains a job to be undertaken in doing a comparative review and evaluation, all in one place, of substantial works concerning the development of the game of cricket from a socio-economic or political perspective. In this Part 2, history graduate Devine McKenzie outlines the kind of considerations or criteria that could be applied to guide such assessments. This reflects her view of what counts as interesting and enjoyable accounts of events and the lives of individuals. |

What was it really like to live in those times or that place, or witness that event?

Sheer inquisitiveness. My five examples:

- Lorna McDonald’s book of 2001,West of Matilda: Life in Outback Queensland from the 1890s to the 1990s.

- Vera Deacon’s book Singing Back the River(2019): a collection of her stories written over six decades, including reminiscences of living on the Hunter River islands and making do during the Great Depression.

- The astoundingly low standard of living and high infant mortality rates of the peasantry of 18th century France. (I’ve mislaid my book with the startling chapter so cannot give the title or author.)

- The Crimean War:1853-56

Territorial ambitions of Russia brought it into conflict with Turkey backed by Britain, France and Sardinia on this peninsular of the Black Sea. Trench warfare saw development of new types of rifle, armoured ships and mines and cost 750,000 lives, two-thirds of them being Russians.

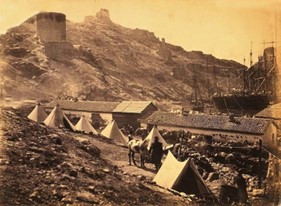

Not only were first-hand reports despatched regularly by William Howard Russell to The Times newspaper of London, there was pioneering photographic documentation by Roger Fenton who roved the front line, travelling around in a converted delivery vehicle with its dark room for developing the glass plates. Some 300 photos survive of the bays of Balaclava port (one being shown below), the camps and terrain of battle, and portraits of officers, soldiers and support staff of the various armies.

The Valley of the Shadow of Death, below, showing a profusion of spent cannonballs in the aftermath of the failed Charge of the Light Brigade.

- Suzanne Lenglen of the world of tennis, a game I play and follow. At Cannes on the Côte d’Azur in mid-February 1926, Lenglen as the undisputed post-War world champion faced the precocious hard-hitting Helen Wills of California representing the next generation. Age 20, Wills already had three consecutive USA Open singles titles to her name and had come close to winning the 1924 Wimbledon singles final against England’s Kitty McKane.

The match in prospect was boosted by a potent combination of extravagant publicity and the machinations of business interests that stood to do well out of it, especially owners of tennis clubs on the Riviera, manufacturers of tennis equipment and those with a financial stake in the casinos and night clubs.

An absorbing and vivid account of the protracted build-up to the match and the play itself occupies eighty pages of Larry Engelmann’s book of 1988, The Goddess and The American Girl, remembered by the overflowing spectators and reporters for what was at stake for Lenglen, the unique atmosphere of the occasion and the ensuing tactical battle. Lenglen scraped through by gaining the second set 8-6 when likely to have gone down in a decider due to her state of exhaustion. Photo below shows the pair with the press just before the start of play. Some spectators can be seen on the roof of the villa on the right, the owner having removed the tiles and charged to provide a view.

At the end, Lenglen slumped in a chair near the umpire’s stand unable to respond to the numerous hands offered in congratulation, her body visibly shaking with the evaporation of tension. It proved to be their sole encounter.

On YouTube there are video excerpts of the match itself so you can witness the style and standard of play, and also Lenglen demonstrating her shots in How I Play My Tennis. Urging you to check these out.

Imagination

- Rather than being concerned with the fictitious, the role of historical imagination is to make the past more intelligible by penetrating the minds and thinking of individuals and the decisions they make.

- Take the perplexing question of why Rudolf Hess – a prominent member of Germany’s Nazi Party – made a wholly unexpected solo visit to the UK during WW2, arriving on 10th May 1941 following some secret intelligence talks on the Continent with German and British Government advisers. Parachuting to ground from his easily recognisable Messerschmitt fighter plane and in Luftwaffe Captain’s uniform, having run out of fuel close to his intended landing site in the Glasgow region, Hess carried with him proposals for peace. Learning of his flight the next day, Hitler went into one of his rages, announced on national radio that Hess was suffering from hallucinations and denounced him as a traitor.

Of the many attempts at trying to understand why Hess acted as he did, the eighteen page essay by historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, containing imaginative speculation, turned out for me to be the most interesting and compelling.[i]

His explanation comes in three stanzas. First, he points to a crucial set of inter-connections. Hess had acted on a lengthy briefing received from Hitler eight months earlier (in late-July 1940) which, by the time of making the flight, was defunct as Hitler had subsequently defused the dreaded prospect of a war on two fronts – fighting Britain and Russia simultaneously. The brief, which Hess accepted as a great honour, was a tricky one: to mobilise certain pro-peace political interests that existed in Britain and oust Churchill and his adherents from office, with the imagined prospect of a German invasion being a vital ingredient in the plot.

Crucially, shortly after briefing Hess, Hitler had cancelled the plan of threatening to invade Britain and had substituted for it a scheme to isolate her through exclusion from the Mediterranean area by capturing Gibraltar and closing the Straits, whilst also forcing her out of Greece. Thereby, the possibility of a return by British forces to the Continent during Germany’s planned campaign against Russia would be blocked, being powerless to create a second front.

Second, Trevor-Roper rejects two hypotheses which have occupied the minds of a number of other historians, finding these unconvincing. One being that Hess was a disgruntled defector to the Allies’ cause as a result of having fallen out from the circle of Hitler’s close advisers and ceasing to hold any Ministerial post, both of which were fact. Instead, he reveals that Hess had come to see himself as a heroic angel of peace, making a bid to halt the hostilities between Britain and Germany and prevent any further loss of life in what he viewed as “an Aryan civil war between two natural allies” – whilst being convinced he was fulfilling the Führer’s continuing wish!

The other one was a conspiracy theory: a cunning plot had supposedly been devised by the British Secret Service to lure Hess to Britain so as to capture him. This stemming from a letter that Hess had indeed sent to the Duke of Hamilton, mistakenly thought to be an influential pro-peace figure, which came to be diverted into the hands of MI5. The conjecture is that its staff used the letter to pull Hess into their net. The potential supporting links and machinations are presented by Trevor-Roper as being too tenuous and far-fetched for this idea to be credible.

Third, as to Hitler’s furious reaction to Hess’ flight, this is taken to be genuine rather than, as some believe, faked in case the mission failed. Not only was there, by then, nothing to be gained from attempting to broker peace with Britain (the proposals Hess brought with him were based on those that Hitler had unsuccessfully tried out in the spring and summer of 1940). There were also a number of serious potential repercussions. Chief among these were disintegration of a mutual defence pact with Italy and Japan which would alarm Stalin, reduction in the morale of German forces, and the risk of Hess under interrogation leaking the plans for the imminent Blitzkrieg operation on Western Russia. As a clincher, Trevor-Roper infers that Hitler would probably have forgotten all about his original briefing to Hess the previous year, partly because it was out-dated by events and partly because in the six months prior to the flight taking place Hitler had very different matters of military strategy to occupy his mind.

The fate of Hess? After being held in custody in Britain, following the Nuremberg trials he would serve a life sentence in Spandau Prison in West Berlin, during which he took his own life at the advanced age of 93.

Interpretation

- Interpretation of past events to help gain an understanding of what has occurred, and to explain why things happened in the way they have, gives rise to the great controversies of history. Part of the fascination of political and diplomatic history is for an outsider to judge which side is closer to the truth. And for many, there is the unsettling feeling of finding both sides highly persuasive!

- Witness the highly divergent and conflicting views of two eminent historians about Hitler’s foreign policy and expansionary campaigns, both having access to the same sources of information. Hugh Trevor-Roper, shown below on the left: Hitler as a master planner, although very deluded, verging on insane. AJP (Alan) Taylor, shown on the right: Hitler as a sane, very clever exploiter of opportunities to extend German power. With plenty of adherents on each side.

To elaborate: according to the “fanatic” view expressed by Trevor-Roper, Hitler was strongly ideologically, if wickedly, motivated and aimed consistently at expansion and war, pointing out that his policy of Lebensraum (making room for natural national development) had been emphasised since the days of his imprisonment and struggle and were seen as necessary for its success – as expressed together with his anti-semitism in Mein Kampf, his manifesto of 1925. In his essay The Mind of Adolf Hitler, Trevor-Roper claims that Hitler had a clear vision which involved a master plan for war and that he controlled the events culminating in the attack on Poland in 1939, although his aims for conquest were not world-wide (as some believe) and were confined to Continental Europe, which vitally included the western, most populous, part of Russia.

The contrasting “opportunist” view, put by Taylor in his book The Origins of the Second World War (1963), is that Hitler had no blueprint for his aggression and territorial expansion. Rather, he was an astute and cynical politician who took advantage of the mistakes and fears of other leaders as they arose, and that his apparent fanaticism was merely a front – an act. On this version, Hitler was in the mainstream of traditional German foreign policy, which had been expansionist in outlook since the second half of the nineteenth century. Also, he expected to get by with a few small wars and hopefully without war at all, whilst pretending for much of the time to be preparing for a great war. Taylor: “He was done for when military strength became decisive, as he had always known.”

A variant on this thesis is Alan Bullock’s Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1952) which portrays Hitler not only as an opportunistic adventurer, but also one who was devoid of basic ideas and beliefs and whose actions throughout his career were motivated solely by a lust for power.

You, the reader, might suppose that differences in nationality or geography account for this strong divergence of views. But Oxford University men all three of them, differing only in their respective Colleges for rooms and regular dinners. In addition, born within eight years of each other.

- Just as polarised are later debates about the treatment of the Indigenous peoples of Australia by European settlers and the respective responsibilities of the British and National Governments. Most notably, Henry Reynolds (shown below, left) versus reactionary defendant Geoffrey Blainey (shown right) and his “black armband” view. Reynolds’ big work is The Other Side of the Frontier (1981), Blainey’s response coming a decade afterwards. Their contrasting positions have been echoed in PM’s political statements, by Paul Keating and then John Howard. There are many other parallels: try the North American Indians.

Revisionism

- Overlain on one or more accounts as time progresses, revisionism is part of the lifeblood of history. Fresh perspectives emerge with reflection or as further information becomes available, often in order to overturn initial propaganda-based accounts that rest on deliberate misinformation.

- I obtained relief, having had an uneasy feeling about the prevailing accounts, on reading Guenther Lewy’s 1978 revisionist treatment of the USA’s twenty year war in Vietnam, and the debunking of George Bush’s stance on Saddam Hussain and the supposed “weapons of mass destruction” (for which read, pursuit of vast oil reserves).

Digestibility & Accessibility

- Sheer bulk tends to be intimidating and is usually off-putting. The Mother of all tomes I have come across is EH Carr’s 14 volumes on Soviet Russia, covering the two decades 1917-39, with three on the Bolshevik Revolution alone. Rather like describing every delivery of a five day Test match, I imagine!

Why do it? Presumably for hoped-for reflected glory in the eyes of other professional historians. Carr did, thankfully, feel obliged to make a summary for the general reader. Even this comes out at 240 pages (paperback edition) and is still a challenge.

- Then there’s Charles Bean, the official historian of Australia’s involvement in WW1, who wrote 6 of the 12 resulting volumes and edited the rest, having been positioned at the front for a good deal of the time. Each volume covers around 700 pages, including numerous maps. Useful if one wants to know about a particular battle or skirmish in which a distant relative played a part, but otherwise…..

- In similar vein, Manning Clark has produced a six volume History of Australia, taking matters up to 1945 (averaging 478 pages per volume)…enough said. Stuart Macintyre has aimed at A Concise History of Australia (4th edition, 2020), but at 420 pages it cries out for a son: A Truly Concise History.

- On the side of the angles is Simon Jenkins with A Short History of England (2011), from start to finish inside one pair of covers. This has a readily digestible 9-13 pages on each era, and 32 chapters in all.

Dating Events & Accuracy

- The focus: minor inconsequential versus fundamental errors, the latter being an author’s obligation to avoid. David Lowenthal (March 2013 article in the news magazine of the American Historical Association) assures us: although regrettably numerous, most mistakes are small details – a wrong page, a misspelled name, a misdated text – minor points that do not materially affect the author’s conclusions or vex most readers. Given the constraints on scholars’ creative time and energy, is it therefore not best to forgive these lapses?

Yet even a fundamental error can be innocuous if it preserves the relativities. Move the actual dates of Bob Hawke’s “promises” to Paul Keating about taking over from him as PM, and of Keating’s responses and planning, by the same amount and nothing is distorted.

“Minor” doesn’t bother me. This doesn’t really detract even if I do tumble to it.

- Relating to accuracy and truth for its own sake is a pertinent comment by the Australian political writer and historian, Keith Windschuttle (in his article, The Real Stuff of History – The New Criterion journal, March 1997):

Those academics who have written in the Rankean mould {following the German historian Leopold von Ranke} are notorious for being boring and soporific. Their focus on getting their facts meticulously right has been at the expense of recreating the grand sweep of the movement of history that less fussy, more literary writers like Gibbon, Macaulay and Michelet managed to achieve. (emphasis added)

Writing Style

- The attractive stylistic versions are exemplified by the one piece of cricket writing that I’ve looked at: Simon Rae’s preface to his biography of the towering WG Grace. Simply captivating, like a perfectly baked rhubarb crumble. It produced a spell of envy.

- Poor style on the other hand tends to block the message, just like a monotone voice of someone giving a talk. It is near impossible to absorb the messages being given out.

Well, I’ve gobbled up the equivalent of seven pages, much against initial expectations! Though I do hope it has given an indication of what many history graduates are about these days.

[i] Trevor-Roper’s essay is one by nine by historians on the Hess affair contained in the 2002 book Flight from Reality edited by David Stafford.

Copies of the book Cricket’s Historians are still for sale through the publishers in the UK, The Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians; and it is being sold also, for instance, by AbeBooks in the UK and by Roger Page of Melbourne.

Leave a comment