A Philosophical Sidelight on Peter Wynne-Thomas’ book, Cricket’s Historians (2011)

Peter Kettle |

A Philosophical Sidelight on Peter Wynne-Thomas’ book, Cricket’s Historians (2011)

Essay by Peter Kettle (Part 1) and Devine McKenzie (Part 2)

Peter Kettle has written biographies of the England cricketer EW Dawson and Randolph Lycett of lawn tennis fame, and interpretive articles on the Test match careers of Don Bradman and Mike Brearley.

Devine McKenzie is a freelance writer who graduated a few years ago with a degree in History from the University of Melbourne.

PART 1 – SOME DIFFERENT THOUGHTS ON PWT’s TREATMENT

- The breadth of the commentary by Peter Wynne-Thomas (PWT) on a multitude of authors’ research and published works – including detailed biographical notes on many of them – is astonishing. In the course of 290 pages (plus appendices), the terrain he covers extends back some 300 years in the case of the UK, and encompasses authors in all the main Test playing countries plus the USA, Canada and a few others. Whilst autobiographies and instructional books are deliberately excluded, this has to rate as a phenomenal feat.

Martin Chandler said in reviewing the book on this website:

Those who are not collectors, but merely have an interest in cricket, and books and bookishness, will learn almost everything they need to know… This book merits a place in the bookcase of anyone with an interest in cricket history and cricket writing.[i]

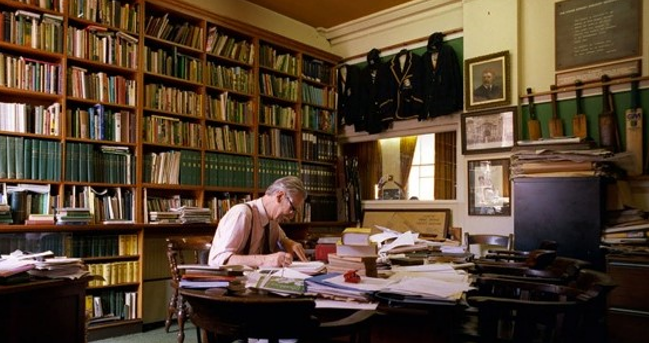

PWT in the library at Trent Bridge

Those reviewers who had some reservations or adverse comments around the time it came out tended to concentrate on what, to them, were significant omissions and its lack of balance in places between different eras. This “philosophical sidelight” takes a different tack.

- PWT’s two and a half page Introduction gives promise of interpretive as well as purely “factual” accounts that build the history of the game – with revisions and extensions as new information comes to light, and as the game evolves and spreads geographically. He observes that “writers on history, in general, not specifically cricket, divide broadly into two groupings”. To paraphrase him: there are those who comb through existing material so as to produce fresh data in their finished work, and those who accept the information already to hand and try to re-interpret it – with a sizeable proportion of cricket’s historians combining both these approaches. In the context of this “sidelight”, it is of interest that some professional historians, such as EH Carr, regard the interpretation of past events and behaviour as the essence of their work – albeit with a satisfactory factual base to work with.[ii]

PWT goes on to note that, besides those engaged in constructing a history of the game, a third group that comes into play, with cricket especially, are “statisticians” – usually in the role of compiling statistical records of players or teams which involves historical research (as distinct from applying formal statistical methods).

- On the interpretive side, one’s appetite is whetted for a discussion of those, on the one hand, who take the line of the renowned historian of foreign policies and international diplomacy, AJP Taylor (1906-90) who, like Herbert Butterfield (1900-79) and Geoffrey Elton (1921-94), emphasises the role of the individual and their personalities in shaping the course of history through their specific decisions and actions; and, in contrast, those historians such as Fernand Braudel (1902-85) and Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) who put most weight on the role of underlying socio-economic forces in the making of history. In the light of PWT’s Introduction, one looked forward to seeing how these two schools of thought might play out in the various endeavours made to trace the history of cricket’s development. However, it turns out that PWT gives the reader very little in the way of explicit consideration of interpretive matters, by far the greater emphasis being given to works to do with the accumulation of statistical material and “factual” historical accounts.

- There are quite a number of historical accounts from a social or cultural perspective on PWT’s radar, most of which necessarily involve interpreting information on events and the motivations underlying individuals’ behaviour. Yet in most cases, these works are either:

-

- Mentioned by PWT with comment that is far too brief, given their importance [iii] – as with Ric Sissons’ well-received book, The Players: A Social History of The Professional Cricketer, 1988 (315 pages). He comments only that “it deals with the contrasting fortunes of amateurs and professionals, and in particular with the post-WW2 ‘shamateur’…and is soundly researched” – though adds, “It is rather let down by a lack of proof-reading”.

In a review of two a half pages in the Journal of Sport History (winter 1989), Charles P. Korr – Professor of History at University of Missouri – notes that “this stylishly written book…demonstrates a vast knowledge of the literature about cricket” and, after pointing to many of the interesting insights, says it “does an excellent job summarising the way in which professionalism became legitimised after the Second World War”. And in the view of commentator/author John Arlott: “It will undoubtedly prove, quite apart from its intrinsic merits, a landmark book in cricket literature”.

A more extreme case in point concerns Gideon Haigh’s The Cricket War, 1993 (326 pages, plus fifty page statistical annex) which won the Australian Cricket Society’s literary award. It attracts the bald comment by PWT: “It detailed the Packer affair”.

For Peter Roebuck, though, it provides: “a fascinating account in masterly detail of an extraordinary episode”. The book’s wide appeal led to it being reprinted in 1994, and republished in 2017 with an updated introduction.

As is common knowledge, Kerry Packer’s revolutionary actions in the late-1970s have been of major significance for the subsequent development of the game. By the time the text of PWT’s book had been completed, day-night ODI matches with white balls – ushered in by Packer’s World Series Cricket program of 1977-79 – were well established, along with widespread use of protective helmets and coloured clothing. Moreover, levels of remuneration had undergone a major uplift, for international players at least. Accordingly, some illuminating comment on Haigh’s book seemed called for.

-

- Or such works are lambasted by PWT – eg two books by Derek Birley: The Willow Wand: some cricket myths explored, 1979 (214 pages), and A Social History of English Cricket, 1999 (374 pages). These works are held in thinly veiled contempt for their display of naivety and ignorance – the latter book “demonstrated that he had learned little from the errors made in his 1979 work”. Yet, Birley’s Social History was acclaimed by the critics when it first appeared, and strongly favourable comment continued when the paperback edition came out in 2013.[iv]

- Or they are dismissed for saying nothing new in PWT’s eyes – eg a substantial history of the earliest beginnings of the game up to the 1890s (and very briefly through to WW1) by former British Prime Minister, John Major – titled More Than a Game, 2007 (397 pages plus appendices),[v] with a paperback edition coming out the following year. PWT’s observation being that “it adds no fresh facts, nor does it pose any new theories with regard to the game’s origins”. In the review on this website, Archie Mac says in a similar vein, though softer: “He fails in providing much new information on the past great events and players of the game.” [vi]

However, the book displays John Major’s scepticism about a considerable number of claims, making out a good case for treating them as being without proper justification, and hence unproven. As many as seven first beginnings of the game suggested (hypothesised) by different sources are considered before being cast aside for lack of supporting evidence, such as:

-

-

- “It is probable that games such as ‘club-ball’ were ancestors of cricket, but they cannot be acknowledged as the game itself, and should not be assumed to be so.”

- “This reference to ‘Kricket-Staves’ (of Queen Mary’s times) is a real trap.” A lengthy following paragraph explains why.

- The claims sometimes made that cricket originated in France are convincingly debunked.

- “I am puzzled by Altham’s assertion in The History of Cricket that ‘with the restoration of Charles II in 1660, in a year or two it became the thing in London society to make matches and to form clubs’. If Altham is right I can find no evidence of it. So far as I can determine there is no record of a cricket match being played in London before the 1700s and no mention of a club until 1722.” [vii]

-

The fascinating first chapter, The Lost Century of Cricket, discloses the spirit of John Major’s approach to addressing the initial beginnings of the game as posited by different writers:

-

- “In the absence of concrete evidence, of documentary proof, of contemporary records…cricket may have been played under another name earlier than we know, but since its birth is shrouded in legend and mystique, we cannot be certain.” He heartily approves of the maxim: “Things not known to exist (on the above basis) should not be assumed to be so”. (page 18)

Some of the claims that he disputes are deserving of the term “decayed” or “moribund facts” – approaching death, lacking vitality or vigour – while those he definitely refutes are deserving of the term “deceased facts”. Logically, is just as important as discovering actual facts! It is a feature that PWT doesn’t draw attention to.

Archie Mac also notes that John Major “pours cold water on many of the accepted canons of cricket history, including what is considered the first written examples of the game – believing the often quoted reference by King Edward I in 1300 of ‘creag’ has no relation to the game we now call cricket, and that the first most creditable reference is not until 1598, by an English coroner.”

On this book in the round, the cricket writer/biographer David Rayvern Allen has said: “I can’t think of anyone else who could have given such an authoritative inner and overview of the game and have the ability and knowledge to put it in the context of cultural, commercial, historical and social happenings at the same time. Thoroughly readable”.

- PWT’s own work on this broad topic (published in 1997), The History of Cricket: From the Weald to The World (250 pages, using generous size lettering) is very much a book for the lay person rather than someone who already has plenty of pertinent knowledge. Of its kind, it is excellent: displaying an easy writing style, containing plenty of illustrations and photos, and is well laid out. Those in depth interpretive histories by John Major and Derek Birley, just referred to, are by no stretch of the imagination rivals to PWT’s own account: they are very different animals.

- PWT strongly plays down the worth of literary quality and easy accessibility of works to the cricket loving general public – both these attributes being a strength in the case of Gideon Haigh’s Cricket War, John Major’s early history of the game, and Derek Birley’s Social History. The term “literary quality” used here to refer to aesthetic matters besides an attractive writing style – the way that material is presented, and the relevance and quality of any photos which happen to be generally poor in PWT’s own book (attracting one reviewer’s comment that a number of them “seem to have taken been by a camera which had spent a long time submerged in water”).

- Another concern is that, with a single exception, criteria are not put forward by PWT for assessing the merits of works of social and cultural history, so as to inform the potential reader. His judgements on the quality of such a work focus strongly on the scope and depth of research undertaken and the accuracy of factual material, to the exclusion of virtually everything else. This raises the question of why accuracy of dates, places, etc actually matters – that is, whether or not it matters in a specific instance, given the theme of the work and the particular context.

- The one criterion that does stand out for PWT (though not explicitly stated), is what is deemed to constitute commendable research. This is evident in his praises at many places in the book and typified by those he most admired – including Frederick Samuel Ashley-Cooper, George Bent Buckley, Edward Eric Snow, Bertram Joseph Wakley, Irving Rosenwater, Gerald Brodribb and Philip Bailey. This criterion is doing thorough, meticulous and unstinting research of an original nature – in essence, a matter of fresh and conscientious digging.

- Closely allied to the point just made is the stress PWT places on the importance of “serious” attempts, as opposed to what are regarded as lightweight (which leads him to praise, for example, some low profile booklets for being “workmanlike and competent”). At page 275, he quotes, approvingly, from a letter received from Irving Rosenwater:

The writing of cricket history is not the cavalier process that some people see it as, to be undertaken at a whim, and just copying what is common knowledge. Some writers go through a whole career on that basis. Cricket history is an extremely demanding branch of scholarship, indulged in alas far too frequently – with predictable results – by persons unfitted for this task. (emphasis added)

- Stemming from PWT’s general attitude is a feature running throughout his book – the irresistible urge to comment on the historical accuracy of a work which is, unfortunately, often done in a vacuum. The problem is that often he doesn’t say whether the errors picked up really are significant ones, given the theme of the work and the specific context. Without such comment, the likely effect is to put off a potential reader owing to concern they will be led up some false trails. In short, there is a near obsession on PWT’s part with accuracy for its own sake.[viii]

To take three examples:

p. 183/4: on Michael Melford, the Associate Editor of a large volume, The World of Cricket (1966), edited by EW Swanton: “His ability to ferret out historical errors in the work of the other contributors to it was minimal.”

p. 128: “A Concise History of Cricket written by SH Butler (published in 1946) was depressingly inaccurate, though only 40 pages in length. The booklet …states that the first overseas reference to the game was in 1670 (in fact, 1676) in Antioch.”

p. 128 again: “William Clarke’s All-England Eleven was said to have toured the country for ‘several’ seasons, whereas in fact the team lasted over 30 years”.

Moreover, faint praise can be disturbing, even damming. For instance, commenting (at page 235) on the first edition of Pelham Cricket Year, covering the 1978 and 1978/79 seasons worldwide: “Its compilation was a mammoth undertaking and relatively error-free”. And (at page 296) on former cricketer Simon Hughes’ deliberately conversational style of history, published in 2009: “It serves as a gentle introduction to the game’s history, with not too many blunders”.

- PWT also displays a terrier-like tenacity for wanting to get to the bottom of a matter and see the truth emerge, without its practical importance being obvious or being brought out by him. This characteristic is demonstrated by his discussion of two particular controversies. One of these is a matter recurring at many places in the book which concerns the date when matches of first-class status began and which matches should rightly be treated as first-class. This is illustrated by:

p. 104: a reference being made to the inclusion, in the Lillywhite annuals of the 1870s, of MCC matches against Hertfordshire and Staffordshire and some others that are of doubtful “first-class” status, and Ashley-Cooper’s decision to follow suit in his book WG Grace, Cricketer: A Record of his Performances in First-Class Matches (published in 1916), “which has caused headaches for modern historians”.

p. 117: in connection with the “first-class” averages given by Frederick Gustard for leading players in the USA, Canada and Bermuda through to the early-1930s, PWT comments: “He takes a much more liberal approach to the subject than later statisticians would… being swayed by the possible expansion and development of top class cricket in these countries” – going on to note that these perceptions would be altered by the Second World War.

p. 130: statistics compiler Roy Webber is roundly ticked off for treating matches played by Northamptonshire before 1905 and by Worcestershire before 1899 as possibly being of first-class status, rather than unequivocally not being so. PWT comments, in withering fashion: “One cannot think of any other ‘expert’ who would remotely believe either county were deemed worthy of such status before those seasons”.

p. 208: PWT draws attention to the fact that arguments about whether or not the “famous” Maharaj Kumar of Vizianagram matches of November 1930 – January 1931 should rank as first-class “have rumbled on ever since the full scores were dug out of the Indian newspapers and printed in the Playfair Cricket Monthly magazine” in England. (These being matches played by a team that toured India and Ceylon, eighteen in all, organised by the wealthy cricket-playing Prince Vizianagram following cancellation of the MCC’s tour of India due to political problems. The Prince recruited England’s Hobbs and Sutcliffe for the tour, respectively featuring in twelve and eleven of the matches.)[ix]

p. 217/8: A whole page worth of text is devoted to the work of the newly formed ACS Committee in producing a Guide to First-Class Matches in the British Isles from 1864-1946 (published in 1976) – with notes on all the “borderline” cases explaining why each of them is included or omitted from the final list.

Whilst exploration of this topic may be of relevance for arriving at an agreed set of consistent and directly comparable statistics for the players concerned, in other respects it would seem to have little importance. After all, the cricket enthusiast can find out who played in each of the “borderline” matches, when and where, and make their own mind up on the significance of individual matches. A classification from “on high” can be regarded by the enthusiast as tantamount to mollycoddling! Even with the ICC’s ruling in 1947 on what shall be deemed a first-class fixture from then onwards, the core of the matter was delegated to the Governing body of each country – ie whether the competing teams are adjudged to be of first-class status.

This has, inevitably, involved an arbitrary (if, perhaps, a seemingly reasonable) demarcation between those teams that have been so blessed and all the rest. In the case of the MCC, it essentially relied on the solution it reached back in 1894, encompassing all the teams of the official County Championship (initiated in 1890);[x] in addition, anointing the Oxbridge sides and those playing some other notable annual fixtures, such as North vs South England and Gents vs Players; as well as deciding to endorse some occasional “Elevens” on the basis that they field mainly players recognised to be of first-class calibre. The overall solution is, of course, the outcome of a series of negotiations with the claims of the various interests concerned and is one that potentially shifts as the structure of the game changes.[xi]

- The other controversy to mention relates to the growth of, and changes to, the lists put forward by historians of past England County Champions, this being one of the projects that PWT was working on shortly before his death in mid-July 2021, at age 86. PWT’s draft material on this matter is contained in the 2022 summer issue of the ACSH journal, giving the ins-and-outs of how far back a county could rightly claim to have come top of the annual England Championship table. This matter has proved contentious at various stages, as indicated by this abbreviated outline of the trail of events:

-

- During the 1860s, some “great rows” occurred with a number of counties refusing to play against certain opponents, most notably during the 1863 season. In light of this, it was thought by Ashley-Cooper – in providing a records section to WG Grace’s 1891 book, Cricket – that a results table for that year would be meaningless. Subsequent opinion among commentators was divided on whether a proper, or official, County Championship table could be said to begin in 1873 or 1875. The esteemed annual, Wisden Almanack opted for the year 1875 in its 1901 edition, but switched to the former date of 1873 nine years later. PWT wrote in his draft: “It is clear from a short article in The Cricketer magazine of 13 June 1953 that at least some cricket followers were not entirely happy that the accepted date of 1873 was correct”.

- In 1963, Wisden put the proper starting date back further, from 1873 to 1864, doing so in light of research carried out by the ultra-thorough, and forthright, Roland Bowen. He had “argued vehemently” for such a change in an article that Wisden itself had published four years earlier (in 1959).

- Nearly two decades later, PWT himself brought together various pieces of research done between the 1820s and 1860s to suggest nominal annual County Champions during that period. However, his article – headed The Early County Championship – appearing in the ACSH journal, December 1980 issue – was unsuccessful in its attempt to extend the list of County Champions back to 1825.

- A truce of sorts was reached in 1986 when the popular Playfair Annual changed its own list of Champions, adopting a starting date as late on as 1890, saying: “The English County Championship was not officially constituted until December 1889”. This seemed like a workable pragmatic solution, as it had simply been impossible to get agreement among those concerned to a definitive list of pre-1890 Champions.

- The saga virtually concludes in 1995 when Wisden decided, unilaterally, to issue two lists that were accorded a different status: “Unofficial Champions 1864-1889” and “Official Champions 1890 onwards”. In a later edition, Wisden reduced commentary on the pre-1890 Champions to a short paragraph, along with a reinforcing note: “These have no official status”. And that is where it has all ended up – Wisden rules!

Whether this issue of legitimacy has really been worth so much argument is questionable. The only practical impact I can think of that the eventual “settlement” has had is the following. Certain counties can now justly claim to have been fully legitimate Champions in some long ago era – which could, with some advantage, be woven into their marketing material, besides being nailed to the pavilion honours board.

- Another matter also gone into in some detail by PWT is a highly specific one. This concerns the true date of a celebrated match arising from Kent’s challenge to All-England (an ad hoc team representing the Rest of England), which was played in Inner London on the Artillery Cricket Ground in Finsbury. Kent won a dramatic contest by a single wicket, despite needing several runs when the last pair of batsmen came together. PWT devotes an entire page to the circumstances surrounding the discovery – made public in the magazine Cricket in November 1898 – that the match took place in the year 1744, and not two years later as stated in Haygarth’s Scores & Biographies as well as in some other places.

Although twenty-nine matches involving other ad hoc teams named All-England or The Rest took place between 1739 and 1778, according to Cricket Archive (internet site), apparently only this one against Kent in 1744 has a surviving scorecard. Yet, it wasn’t the first such match in which a county side is known to have emerged victorious. Kent had narrowly done the trick in the initial All-England match in early-July 1739, held on London’s Bromley Common. So why the match of 1744 is regarded by PWT as famous, and the date deserving to be precisely pinned down, is unclear to the non-expert – unless this is due to its advance publicity and high spectator numbers.

Such a challenge by a county side became by no means unusual. Eric Snow’s initial volume of Leicestershire cricket history contains the scorecard details of a two innings, eleven each side, match between Hampshire and All-England played in mid-July 1790 – contested for a sum of 1,000 guineas – with the County winning by seven wickets. (The match being held at Burley-on-the-Hill in Rutland, now part of Leicestershire.) “There was a splendid Ball afterwards and the magnificent ballroom in the House (of the Earl of Winchilsea) must have presented a noble sight.” [xii] Snow also notes that in early-August 1793, Surrey played England – another two innings, eleven a side match, also staged at Burley (Surrey losing by seven wickets). The scorecard is, again, reproduced.

- And discovered “truths” should not be go unobserved, or be treated lightly. PWT is intolerant – sometimes outright disdainful – of those who overlook or are careless with the true facts, brought into being – often with much toil – by faithful researchers. A military analogy is of Generals being careless with the well-being – even the lives – of soldiers in carrying out their war plans. In this connection, PWT notes (at page 284):

A major flaw with many of the Famous Cricketers books, especially the earlier ones, was that the authors frequently based their statistics on match scores printed in Wisden, even though the actual scorebooks for many of the matches were extant. Geoff Wilde, who used Lancashire scorebooks for his volumes, unearthed no less than fifty differences between the scorebook and the score printed in Wisden.

- In conclusion: there remains a job to be undertaken in doing a comparative review and assessment, in one place, of substantial works concerning the development of the game from a socio-economic or political perspective – applying the kind of considerations, or criteria, that are suggested in Part 2 by Devine McKenzie, to be posted next week.

NOTES

[i] Review was published on 12 February 2012.

[ii] Edward Hallett Carr, What is History? (Second Edition, 1987)

[iii] An exception is the two and a half pages that PWT devotes to discussing Rowland Bowen’s history of world cricket, published in 1970: comprising 238 pages (plus three appendices giving the dates of key events). It is titled, Cricket: A History of its Growth and Development Throughout the World, published by Eyre & Spottiswoode, London.

[iv] See, for instance, the review by Nicholas Lezard in the UK’s Guardian newspaper, 26 July 2003; and Christopher Hirst in Britain’s on-line newspaper, The Independent, 30 August 2013.

[v] All bar 15 pages of John Major’s 397 page text are taken up with developments prior to 1900.

[vi] Review published on 2 August 2007.

[vii] Of other cases of scepticism I noticed in reading John Major’s book, one concerns the birth of round-arm bowling and the widely accepted and charming, “though dubious”, story relating to the keen cricketer and landowner John Willes, who practised in a barn with the assistance of his sister Christiana and a ball-retrieving dog. “She threw the ball to Willes round-arm since her voluminous hooped skirts prevented her bowling in the familiar underarm fashion” – a tale that “cannot be disproved, nor can it be relied upon”, as in the period concerned, between 1800 and 1806, “hooped skirts were no longer in vogue.” (p. 126/7)

[viii] PWT’s near obsession with getting at the “true facts” reflects a large part of his cricket research and writing career which spanned more than three decades, as outlined in the three page Appendix by former colleague Keith Warsop. PWT was involved in creating various information bases such as players’ seasonal averages, producing statistical and biographical portraits of individual players – notably Nottinghamshire Cricketers 1821-1914 (published in 1971), later extended to the 1919-39 period. Such endeavours eventually displaced PWT’s professional job as an architectural consultant.

As Warsop also notes, PWT was centrally involved in many ACS publishing ventures: checking and sub-editing the early booklets and contributing a number of works himself. He collaborated on the large work, Who’s Who of Cricketers (published in 1984) which gives bibliographical details of British first-class cricketers from 1864 onwards, and he produced volumes on the county cricket histories of Nottinghamshire, Hampshire and Lancashire.

[ix] Nine of the thirteen Vizianagram matches that featured either Hobbs or Sutcliffe, or both of them, are now regarded by Cricket Archive and most sources as having first-class status.

[x] Had the proposals of the County Cricket Council (itself formed in the late-1880s) for a three tiered division of counties been adopted, it is likely that those counties below the first division would have been denied first-class status – a move blocked by the second tier candidates in late-1890 after fierce argument. In effect, the proposed third tier would later turn into the formalised “Minor Counties” competition (beginning in 1895 with 14 teams).

[xi] With the County Championship being split into two divisions from 2017, logic suggested that those teams of the lower division should, potentially at least, be regarded as below first-class status, though through their combined negotiating strength they have clung on to the former entitlement – which is to be regretted.

[xii] EE Snow, A History of Leicestershire Cricket, from the early days through to 1948 (published by Edgar Backus, Leicester, 1949). Later in his book, Snow reports on Leicestershire County fielding 22 players against an All-England Eleven on five separate occasions between 1849 and 1867, including a victory for the County in 1860. A number of the many other matches played by an All-England Eleven are mentioned in Ric Sissons’ The Players, and Birley’s Social History, referred to earlier.

Copies of the book Cricket’s Historians are still for sale through the publishers in the UK, The Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians; and it is being sold also by, for instance, AbeBooks in the UK and Roger Page of Melbourne.

Leave a comment