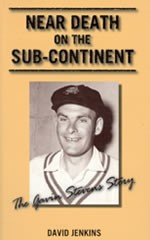

Near Death on the Sub-Continent

Martin Chandler |Published: 2009

Pages: 183

Author: Jenkins, David

Publisher: Cricket Publishing Company

Rating: 3.5 stars

This is the dramatic story of Gavin Stevens, a South Australian opening batsman, who made his First Class debut in the 1952/53 season. By 1959 Stevens had done enough to earn selection for the team that was to tour both India and Pakistan under Richie Benaud later that year and it was in India that his cricket career ended and he almost lost his life.

Stevens’ career was not a long one. He played just 47 First Class matches all told including, on that ill fated tour, four Test matches. Whether he might otherwise have gone on to be one of the leading batsmen of the 1960’s is a matter of conjecture but the purpose of David Jenkins’ book is not to examine whether that is the case rather it is to record one of the more interesting tales from cricket’s long history which, thankfully and not a little fortuitously, is not a story that ends in tragedy.

The title of the book arises out of the fact that on the Indian leg of the tour Stevens contracted what turned out to be hepatitis A. The effect on him was so pronounced that he was hospitalised in India for 11 days and it seems his life was in the balance before the timely intervention of an expatriate English doctor. Stevens’ recovery was slow and while at the age of 77 he enjoys good health in peaceful retirement on Queensland’s Gold Coast he never played cricket at the highest level again.

Author David Jenkins’ previous excursion into cricketing biography was a short memoir of another Australian opening batsman, Ken Eastwood, who played one Test in 1970/71 and which is reviewed elsewhere on the site. He is a good writer with an eye for an interesting subject and he tells Gavin Stevens’ story very well. The early part of the book can be somewhat laboured in that Jenkins goes through Stevens’ First Class appearances on a match by match basis. Although I can see that there is more merit in that approach for a Gavin Stevens than for men with lengthier careers it does tend to be heavy going given that most of the matches themselves were unremarkable.

I was also slightly disappointed in the way in which hepatitis and its various strains were explained. I came to the book knowing very little about the disease other than that it was something to be feared and while, having finished the book, I am rather better informed now I do feel that, given the central importance to Stevens’ story of the disease, that a digression, perhaps written by somebody medically qualified, would have been a more valuable addition to the story than simply quoting the relevant entry from Wikipedia.

The part of the book which does have the main interest is, of course, that 1959/60 tour which has never been fully chronicled, and its aftermath. Jenkins does not seek to produce a full account of the tour but it has obviously been thoroughly researched, all the important people have been spoken to and the picture it paints of the difficulties of touring in the sub continent half a century ago is a fascinating one. Equally interesting are the financial pressures which, as much as the legacy of his illness, caused Stevens, once his health began to mend, to decide that his cricket career was over.

The reflections of Stevens himself, about both his own times and today’s, conclude the book and set the rest of the book nicely in context. I do not suppose there will be a great rush, outside the ranks of the usual cricketing bibliophiles, to buy a book which deals with such a neglected corner of cricket history but it is not expensive, can be readily obtained through specialist dealers in Australia, and is certainly recommended to anyone who is curious about its subject matter.

Leave a comment