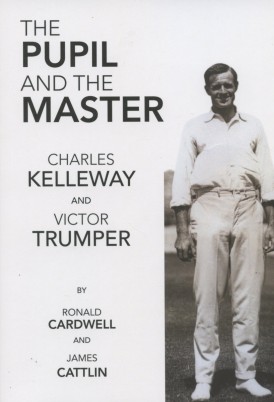

The Pupil And The Master

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 115

Author: Cardwell, Ronald and Cattlin, James

Publisher: The Cricket Press Pty Ltd

Rating: 4 stars

The sub-title of The Pupil And The Master is Charles Kelleway and Victor Trumper, but it should not be inferred from that that this is another book about the iconic Australian batsman of the Golden Age. In fact it is a reference simply to the fact that Kelleway and Trumper knew each other well, played together for Australia and New South Wales and opposed each other in grade cricket. On a sadder note Kelleway was one of those who carried Trumper’s coffin at his funeral.

The book is therefore entirely appropriately categorised as a biography of Kelleway, a man capped 26 times by Australia either side of the Great War, but a name seldom remembered today. After reading this joint biography from the pens of Ronald Cardwell and James Cattlin one thing that is certain is that Kelleway does deserve to be remembered for rather more than the distinction of being the only man to have played Test cricket with both Trumper and Donald Bradman.

As far as why Kelleway’s name has faded from prominence is concerned that is, presumably, because the way he played the game does not sit comfortably with the common perception of what happened in the Golden Age. As a right handed batsman he seems to have been somewhat dour in his approach with a limited range of strokes, and as a right arm fast medium bowler his stock in trade was accuracy and economy rather than an ability to run through sides. His Test career averages of 37.42 and 32.36 demand respect however and, at the time of his retirement, only fourteen Australians had been capped more often.

Those bare facts clearly justify a biography for Kelleway and the track records of Messrs Cardwell and Cattlin certainly suggested that they were the right men to embark on the project, so I opened the book with much anticipation. For a while I thought I might be disappointed, but this one is a book to be persisted with, and after the first few relatively uninspiring chapters The Pupil And The Master develops into an excellent read.

It is not that there is anything particularly ‘wrong’ with the initial chapters, so much as there clearly wasn’t a great deal to find out. Those records there are have clearly been fully utilised, and the press reports of the time, both for Kelleway’s First Class and Grade appearances, have been consulted. The problem is that there is not a great deal else so, whilst there is no unnecessary tedium or repetition the reader gets to the cessation of the Great War feeling that whilst he knows what Kelleway had achieved on the field and his strengths as a player, Kelleway the man is still a mystery.

I would have liked to have known a little more about Kelleway’s war service, although I cannot imagine that anything would’ve escaped the authors’ attention. A couple of letters home from the front have been located, and a broad picture of what Captain Kelleway got up to emerge although how, where and why he ended up being wounded on three occasions and gassed on another is not entirely clear.

The narrative moves smoothly up through the gears as peace returns and Kelleway is selected to lead the Australian Imperial Forces side that was quickly put together to tour England. Forty years ago Cardwell’s first book appeared and it was and remains the only book on that most interesting of tours. Kelleway’s tenure ended early and nothing in the years that have passed have shed any further light on why that was the case. Kelleway was not, it seems, an easy man to like and that unpopularity and its effect on team spirit becomes a recurring theme.

The ever present Kelleway made significant contributions to Australia’s Ashes successes at home in 1920/21 and 1924/25, but he didn’t tour England and South Africa in 1921/22, nor England in 1926. There were, possibly, cricketing reasons, business reasons or those issues that had caused the clouds to gather over that AIF tour in 1919. Definitive explanations are elusive, but the evidence is carefully marshalled and examined.

Despite his not being selected for the 1926 trip Kelleway was nonetheless in England, as a member of the press, and after a variety of clerical positions for a number of employers that became his profession. The leaving of a body of writing is, naturally, a boon for biographers and although, despite those aspects of his character which might have counted against him at times, Kelleway’s writing certainly seems to be measured in tone and clearly demonstrated the sort of acumen that led to his being asked to lead the AIF side in the first place.

Kelleway married in 1922 and his only child, son Ivor, was born a couple of years later. Sadly Kelleway died at the early age of 55, and Ivor passed away in 1992 but he too had a son, Christopher, and he is alive and well and made himself and his memories available to Cardwell and Cattlin. His input coupled with his grandfather’s writings enables the co-biographers to produce what is ultimately a full and rewarding account of an interesting cricketer.

The main feature of any book is the quality of the writing and how interesting the subject matter is, but as with anything from this publisher The Pupil And The Master is much enhanced by the quality of the paper it is printed on, of the photographs and other illustrations, the unconventionally set out statistical summary and a ‘proper’ index.

Leave a comment