Another Look At “Cricketing Caesar”

Peter Kettle |

Following Martin Chandler’s review in May of Mark Peel’s biography of Mike Brearley (JMB), this supplementary review article focusses on three particular matters that this stimulating and thoroughly enjoyable book brought to the forefront during my reading. I should add that whilst it is an “unauthorised” account, Peel’s discussion of JMB’s upbringing, his time at Cambridge and also the chapter On the Couch read as though he had access to a number of JMB’s personal documents. And it has a mouth-watering eleven page Introduction.

JMB as a Captain – in Tests and for His County

I read the consideration of JMB’s captaincy having had a careful look at his record in relation to those adjacent Test captains (1969-88 period) and all others of post-WW2 times. Suffice to say that, in whatever way one examines this (versus Australia, versus Pakistan and India at home and then away, and so forth), he comes out exceptionally well on win to loss ratios and also on the relatively low proportion of drawn matches that were not due to rain.

Without dwelling on these comparative statistics, Peel handles the dual aspects of JMB’s captaincy admirably at both Test and county level, with discussion entering at various parts of the book. On player management and motivation, he largely lets the players themselves do the talking. Illuminating comments are given on the Test arena from, for example, Mike Hendrick – making you feel you were the only person capable of doing the job he wanted done at that specific time (p225) – Graham Gooch, on his ability to relate to all types of people (p224); David Gower on empathy for his own players (p225); and Ian Botham on effective communication and commanding respect (p231). Even the prickly Geoff Boycott – who coveted the captaincy role but messed up on his brief go at it – confessed: “His attitude {towards me} was balanced and honest….I felt that Mike understood me”. (Page numbers being cited as the book has no index.)

These comments, often quoted verbatim, from the great and the good – and others besides – are usually placed in the context of a particular match or series, or the player’s overall career. All summed up by Rodney Hogg’s pithy phrase that “Brearley has a degree in people.” Only Phil Edmonds is identified as being a glaring exception, often at loggerheads with JMB both on and off the field, which once nearly ending in a physical brawl!

At county level, Peel tells the story well of JMB being confronted with the scepticism and resistance of the old guard to his unconventional ideas when appointed as Middlesex captain (with the decisive backing of Gubby Allen, also ex-Cambridge) and his endeavours to ultimately get each of them on-side. JMB had to convert, most notably, the seasoned Test players, Titmus, Murray and Parfitt (9, 7 and 5 years his elder), having worked their way up the traditional way on the ground-staff with various mundane tasks to perform to boot. In contrast, a number of the youngsters during JMB’s early times as captain expressed their appreciation – such as Simon Hughes, encouraging him to go all out for wickets; and Mike Gatting, surprised and dead chuffed that his opinion was sought on occasion about what to do when in the field. Some players on the way up are quoted for being given recognition and being helped – such as Roland Butcher, getting public credit for his observation about the team’s lack of focus and making you believe in your own ability. Middlesex’s recruit from South Africa, Vincent van der Bijl was full of praise for JMB’s efforts to help players attain their own aspirations within the body of the team.

Turning to the flip side of captaincy, tactical nous, this is handled with a number of well chosen instances of JMB’s decision-making, again mostly through the perspective of individual players – including some opponents as well those of his own teams. For instance, there is Brian Rose of Somerset (p143) who learned from JMB about the importance of thinking well ahead – where a captain wants to be in five or ten overs time and letting his bowlers know of this. One perhaps little known ploy that is noted is JMB occasionally using Boycott’s medium pace deliveries as an attacking weapon in Tests. Australians aren’t generally known for complimenting opposing counterparts, but Kim Hughes is quoted for considering JMB’s captaincy to be outstanding during the 1981 Ashes series – sufficient to deny Australia the series win they were set up for. In its aftermath, even Dennis Lillee was moved to say: “From an opposition player’s point of view, it was obvious that his tactical manoeuvres were of an exceedingly high standard.”¹

And the doyen of commentators, former Australian captain, Richie Benaud singles out JMB’s ability to gauge the strengths and weaknesses of the opposition and being confident enough to go with his hunches. Peel lets JMB make the point that, once a decision is taken about a bowling or field change, the result is largely (though certainly not entirely) out of the captain’s hands.

There is rather less material on JMB’s tactical ability than managing players which is in order given the thorough treatment of it in his own widely acclaimed book, The Art of Captaincy. First published shortly after retiring with a new piece, In Retrospect, for the 2001 edition giving a psychoanalytic angle on the role; and a further edition in 2015 with a substantial interpretive Foreword by Ed Smith (another former Cambridge and Middlesex batsman-captain, retiring in 2008 and now the chief national selector), plus a new Introduction by JMB himself which subtly underlines the relevance of the book’s unchanged body for present times. Collectively, Peel’s portrayal of his tactical ploys give the lie to a traditional Australian view that captaincy is very largely a matter of luck. Peel makes us realise that this may be true of run-of-the-mill Test captains but not of the outstanding ones.

Yet the reader doesn’t go away with an all-sweetness-and-light version of JMB in the captaincy role. Peel reveals his toughness with his players when called for, Botham included. As for opposing teams, JMB was keen on sledging, often orchestrating audible chatter in the slips cordon about a batsman’s weaknesses; sledging done in a more subtle manner than normal! Among controversial ploys that Peel reveals is having a bowler deliver a series of lobs that appear to the batsman to be dropping near vertically out of the sky, being both difficult to swot and embarrassing if he fails to do so. Another is JMB putting himself on to bowl a couple of overs of underarm when captaining Cambridge in the annual varsity fixture, arriving as grubbers, having tried this out against Sussex earlier that season.

As well as this kind of innovative streak, we learn of a “ruthless” one in striving to win. JMB’s hard-line attitude is exemplified by praising a bowler who directed vicious bouncers at a nightwatchmen who hung around (resulting in a negotiated pact with the opposition). Wicket-keeper Roger Tolchard is called upon, reckoning that JMB was the hardest man he had ever played with, and “clever enough to know how to be nasty and cruel!” In short, happy – indeed keen – when circumstances “called for it” to play to the very limits of the rules.

JMB as a Test All-Rounder

JMB was a highly effective all-rounder for Middlesex in his captaincy-opening the innings roles, having seven big seasons with the bat, six of these when captaining the side and usually opening the batting (1974-75, 1977 and 1980-82). He was also a competent wicket-keeper, as shown in his time at Cambridge University – later able to deputise for John Murray, and later Paul Downton, if they happened to get injured during a match.

Whilst Peel leaves us in no doubt about this, some assessment of JMB as an all-rounder at Test level seems in order. Having played himself in, reaching 20 on twenty-three occasions during his 66 innings, he went on to make nine scores of fifty and above – including 74, 81 and 91 when opening the innings – plus four scores in the mid to high-forties.

I feel an opportunity is missed to examine if JMB’s batting – in conjunction with his success as captain – could be interpreted in a way that might conceivably rank him as a genuine Test match all-rounder. Peel could have addressed questions such as: how many of his scores in the mid-forties and above were made against elite bowlers; how valuable were those innings to the team given the state of play at the time and the match outcome; did he have some telling opening partnerships? A number of JMB’s innings do seem to have had a significant influence on the match outcome, such as in the 5th Test in India in February 1977, the 3rd Test at home against Australia in July 1977, the 2nd Test in Pakistan in January 1978 and the 4th Test against Australia in 1981. The conclusion to be reached, whether negative or positive, would I think be of general interest.

I have been intrigued enough to take up this Test all-round question in a journal article to be submitted, viewing JMB in relation to a selection of leading Test batting-pace bowling all-rounders.

Assessing JMB’s Unfulfilled Potential as a Test Match Batsman

JMB reproaches himself about his batting career in a number of respects in his books On Form (2017) and On Cricket (2018), as well as in some newspaper articles. He does so for being unjustifiably arrogant following his success at Cambridge, for being naïve about the demands of Test match cricket on entering the big stage, for ignoring good advice, being a slow learner from his own experiences and suchlike.

Peel asks whether the severity and number of these reprimands has really been warranted which soon, inevitably, leads to consideration of JMB’s unfulfilled potential as a Test level batsman – being the subject of the seven page Chapter 13. He takes it as an accepted fact that JMB didn’t fully exploit his abilities, and seeks to judge the scope and extent of this. Part of the context is JMB’s statement, made in recent times in light of what he learned from his playing days, which Peel quotes: “…I might now be better able to encourage the modest batsman in me to do moderately well in Test cricket rather than poorly.”

Based on the three overall observations below about his Test innings – 66 in all, in 39 matches covering ten series, at an average of 22.9 – Peel comes to a gloomy conclusion:

- The fact that JMB only twice averaged over 30 for a Test series (38.0 and 34.2).

- “The majority of his nine fifties lacked sparkle”, being characteristic of his overall slow scoring rate (28.9 runs per 100 deliveries), and

- “His figures suggest a remarkable consistency throughout his Test career.” Adding that at no particular stage did they differ markedly from his general norm, and nor did he particularly succeed against any one country.

The last two contentions are borne out by close examination. On a standard statistical test of variance about an overall average value, the extent of JMB’s variance in his individual Test series averages is substantially lower than for each of the eight batsmen who usually opened in Tests for England during the 1970s and ’80s (applying a minimum of six series and 40 innings).²

As to JMB’s scoring rate, when making scores in Tests in the 40-80 range, he was one-fifth slower (runs scored per 100 deliveries) than the same eight comparators combined when they also scored in that range. And he was slower than all of them individually, though very similar to both Tavaré and Boycott; taken over all his Test matches, JMB was nearly one-third slower than the rest of the team taken together. Also, his scores of fifty plus came at 31 runs per 100 deliveries, little different to his average for all his innings, with his highest three scores being generated at no more than a moderate rate (38.4, 35.1 and 34.8 runs per 100 deliveries). On JMB’s own admission, he never took full control of the bowling.

Without using the term explicitly, it is clear that Peel comes to rate his unexploited Test batting potential as small rather than substantial/sizeable. Importantly, Peel bases his judgement solely on what JMB actually did in Test matches and disregards indications from his performance in other matches when confronted by international standard bowlers playing in England’s county championship, including those of overseas touring sides. This seems to me an unnecessarily restrictive approach to assessing someone’s potential. Peel doesn’t say anywhere that he is departing from what is usually meant by the term “potential”, being on the lines of a player’s latent abilities that might be developed, and what they are feasibly capable of achieving.

At this point, I am going to indulge in artistic license by devoting a few paragraphs to some of JMB’s more successful times with the bat against high calibre bowling outside of Test matches. This is of crucial importance to the following discussion of how JMB himself, and then Peel, interprets his poor overall performance in Tests.

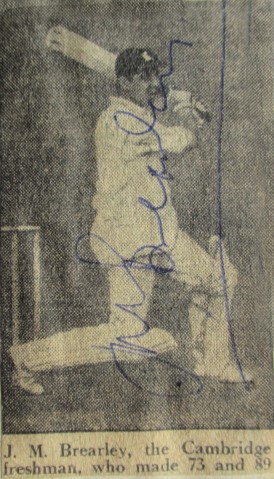

With the bat for Middlesex, JMB had seven big seasons, all during 1974-82 – four times averaging in the mid-high forties and three times in the mid-fifties – usually flowing and fluent after getting established. In four of those seasons he featured among the top twenty players in England on first class averages (not counting members of touring squads). He had shown much promise early on: including as a freshman at Cambridge, in May 1961 making 73 and 89 against the Australians; and for Middlesex in 1964 making an undefeated century against them when demonstrating his high capability facing spin – “playing some exquisitely polished strokes” (The Times).

For Middlesex against other counties, when opening the innings JMB made 15 centuries during 1975-77 and 1980-82 against ten different overseas Test bowlers and four different England Test bowlers, all when in the prime of their careers.³ JMB also did very well for Middlesex playing some of the touring sides. Against the West Indians in 1973, coming in at number 3 and making 87 and then 70 not out, dealing with Holder, Boyce and Shillingford and the off spin of Lance Gibbs; and when playing them again in 1976, making 62 in a second innings opening stand of 131 with Mike Smith – fronting Andy Roberts and Collis King – to set up a notable victory by 4 wickets. Also, a month before his recall to Tests in July 1981, JMB made an undefeated 132 in the second innings against the Australians “with the best batting of his career”, dealing with Dennis Lillee, Rodney Hogg, Geoff Lawson and Ray Bright.

For the MCC, in late-April 1965 playing Yorkshire, making 90 when opening and carrying his bat – early on, hooking Fred Trueman for 3 successive boundaries – to bring MCC level on first innings with a total of 197. And when back again at Cambridge University, in May 1966 making 101 opening the second innings, countering Trueman, Illingworth and Don Wilson; the next highest score that innings being 47.

For England, in the one-day series of 1977 against Australia, in an opening stand of 161 with Amiss, making 78 from 113 deliveries facing Thomson, Dymock and Pascoe plus the spin of Bright and O’Keeffe. Also, when opening for an England XI against Victoria in Melbourne in November 1978, making an unbeaten 116 in a total of 241 for 8 declared, facing Alan Hurst (fast) and Jim Higgs (leg break-googly).

JMB also demonstrated that he could score at a decent rate against strong bowling, especially in pursuit of a target, as these examples illustrate:

- For MCC X1 vs the touring Australians in 1964: set to score 228 in 2.5 hrs, with a full range of strokes JMB, with Boycott, had “a scintillating opening stand” of 121 made in 84 minutes – countering Graham McKenzie and Neil Hawke.

- For MCC vs Leicestershire in 1976 – chasing 325 to win, JMB with Amiss had an opening stand of 301 made at 4.3 per over, disposing of Paddy Clift and Ken Higgs.

- For Middlesex vs the touring West Indians in 1976 – set 274 to win in 5.5 hours, an opening stand with Mike Smith of 131 (JMB making 62) paved the way for a victory – this time countering Andy Roberts and Collis King.

- For Middlesex vs Surrey in August 1977, after a gambit of a one ball declaration on a difficult rain-affected pitch, then (with conditions improved) needing 139 to win in 88 minutes, JMB and Mike Smith “set about their task with gay abandon, plundering 47 runs from the first seven overs, and putting on 101 for the first wicket. Thereafter the result was barely in doubt…”.

This account amply demonstrates that when batting high in the order JMB could handle Test-class bowling and often come out well on top. Peel has plenty of references to his good scores for Middlesex, but most are very brief. He comments in some detail only on a handful of JMB’s many successes in county championship matches against such bowling, most notably from the mid-1970s onwards.

It is clear, then, that something must have gone very wrong when JMB batted in Tests. The big question, which Peel does address, is what happened to drag down his form and result in generally low scores? The role of captaincy didn’t weigh down his batting, judging by his similar pattern of scores and his average before and after taking it on: 24.3 pre versus 22.5 post.

First, JMB’s own view. Peels notes that he never felt he truly belonged on the big stage when at the crease. A feeling of inadequacy came over him in such company, and he never had a solidly successful series with the bat to shed that feeling. Although the reasons for this “not belonging” state of mind are not given explicitly, Geoff Cope – who played with JMB in Pakistan – recalled “he tended to look around at some of the players who were with him who were better than he was. He was finding that part of it demanding.” Opening the batting in the majority of his 39 Test matches, JMB started by partnering John Edrich (who made 37 and 76*) and soon moved on to Amiss (5 matches), then Gooch who was recalled after a false start three years earlier (3 matches) and Boycott (13 matches). The last three rarely failed in both innings when opening with JMB, and respectively averaged 46.0, 55.0 and 59.9 for those innings – dwarfing JMB’s own average when partnering them. The disparity was sufficient to induce JMB to bat in his last nine Tests mainly in the middle order.

To heighten JMB’s task with the bat, he arrived on the Test scene late in his career, at age 34, with excellent form for Middlesex during the previous season. He had also made two centuries and two fifties in the matches prior to his debut in early-June 1976; plus a composed and staunch innings of 36 for the MCC against the West Indians, lasting for nearly three hours, when fronting up to Roberts and Holding – this being shortly before the team for the first Test against them was chosen. The selectors expected him to succeed straight away. He wasn’t given time to settle in the team, and was unluckily dropped after his second Test having made a valuable (if very slow) contribution in the first innings by scoring 40, and sharing a 84 run stand with Brian Close after the side were in difficulty at 31 for 2. Of the other six openers tried in that match and the rest of that series, only Amiss did any better than JMB.⁴ Compare Colin Cowdrey’s experience. He was apprehensive and felt out of his depth when taking each step up from schoolboy ranks through to the Test arena, but was eased in to both county and Test cricket when young.⁵

JMB’s “not belonging” feeling in Tests, while also badly wanting to do well, resulted in him experiencing an abnormally high degree of tension when batting (and was acute during the few days leading up to his debut). It was, as Peel notes, a tension that never left him when at the crease. His mental tension translated into a way of making strokes in Tests that has been variously described as somewhat mechanical, rigid or stiff. He soon became over-anxious to prove himself and worried about failing. “…in Test cricket an inner voice told me that I had no right to be there. I would then become more tense, try harder than ever, and play further below par” (p 182). In trying to minimise the risk of giving up his wicket, JMB also became highly cautious, as John Arlott has highlighted: “Although he often batted freely and fluently in county cricket, when he played for England anxiety drove him constantly into over-care…this frequently cost him his wicket.”

As JMB put it in his recent book, On Form, a concern about the prospect of failing tends, in turn, to create the outcome that we most fear. We create the very thing that we strive most to avoid happening (Chapter 16). An example is his Test innings of 91 in India. Having established himself and playing well he got bogged down; after being dropped on 87, scoring just four more runs in 85 minutes. Another case is his Test innings of 74 in Pakistan which came to an end when trying passively to bat out the final half an hour in order to remain undefeated – the match by then already destined for a draw.

Peel takes a contrary view to that of JMB. He downplays the effect of his “not belonging” and associated tension: “A niggling doubt that he wasn’t fit to play in such company…may have simply reflected Boycott’s crushing assessment that he lacked Test class” (p307). Peel contends that technical problems have been the prime cause of JMB’s low scoring and that he basically wasn’t up to it – hadn’t got it in himself. He also notes a run scoring limitation of a lack of back foot shots against high pace – though Peel praises his “rasping square cut” and his hooking once confidently helmeted (as from the 1978/79 series in Australia, previously using a less protective small plastic skull-cap in his four series during 1977-78).

He cites Tony Lewis who played very successfully in the Cambridge side with JMB in 1961 and captained him the following season (p181). In his memoirs, writing: “I knew him from Fenner’s (the University’s home ground) as an excellent player, but saw at the higher level one technical flaw that denied him many big innings…his right shoulder came around strongly and opened him up to the bowlers.”

This “opening-up of his body” – particularly against pace bowling when defending on the back foot – was a trait throughout JMB’s career. In Tests in England, I find this resulted in him being caught by the wicket-keeper or in the slips from pace bowling in 20 of his 36 dismissals when scoring under twenty runs (spin dominated in his Tests India and Pakistan). This is a high ratio, equivalent to 5.5 innings in every 10. Peel draws attention to this in general terms: JMB being “liable to get out to a good ball defending…always more vulnerable to pace than spin…his chief nemeses invariably getting him caught behind or at slip” (p180).

The “opening-up” trait seems to have been exaggerated during Test matches under the associated tension. Taking JMB’s dismissals under 20 from pace bowling: for Middlesex during his period playing Tests (1976-81), he was caught by the wicket-keeper on 33% of those occasions (15 from 45) whereas in Tests in England this happened on 42% of such occasions (13 from 31) – an appreciable increase.⁶ Some commentators have suggested that the high tension may have inhibited JMB’s footwork, which would have contributed to the higher incidence of wicket-keeper catches from pace – highly plausible!

Geoff Boycott is quoted by Peel in support of his case that technical problems were at the root of JMB’s poor Test record: “He tinkered with his style, his stance, his back-lift, but nothing really worked. That did not surprise me, because it was all too manufactured” (p11). Yet there is no mention anywhere in the book of JMB seeking concerted help for his problem of “opening-up” to the bowler.

Peel also draws attention to JMB’s over-tight grip on the bat handle which hindered him. Well before the time he began playing Tests, he had acted on the advice given by former Warwickshire stalwart opening batsman “Tiger” Smith, at start of the 1974 season, to lighten his grip and relax his arms, which soon led to a sustained improvement in his scoring. However, during the 1978 season Ian Botham noticed that his bottom hand grip was still tight enough in Test play to inhibit his ability to play lofted drives over the in-field – something JMB very rarely managed to do during his Test career. Whilst this somewhat restricted his run-getting, it didn’t contribute directly to his dismissals. If Botham had a Latin phrase book handy at the time, he could also have usefully reminded this former Classics scholar of Virgil’s saying: audentes fortuna iuvat⁷.

I find Peel’s line of argument to be unconvincing. It doesn’t square with JMB’s emphatically demonstrated capability against Test standard pace (as well as spin) outside of Test matches themselves. He simply made too many high scores when playing against such bowling from the mid-1970s onwards to have an ingrained flawed technique, as distinct from a tendency of “opening-up to the bowler” that became greater under high stress. In my view, JMB’s Test match potential comes down, in large part, to whether he could – with help – have resolved his mindset issue, as this would also have partially cured his “opening-up” through employing resulting tension-freed footwork.

The obvious question now surfaces: what could JMB feasibly have achieved if he had taken sound advice at the outset of his Test career for that technical weakness and his inhibiting frame of mind? Peel notes that the technical help JMB did get amounted to little more than a series of tips from different people, some of it conflicting, and didn’t get continuous help from any single trusted individual. JMB regretted his failure to find a mentor.

A preliminary matter is whether suitable help could actually have been obtained had JMB sought it. It was the early days of sports psychologists, so finding a suitable one might have been difficult.⁸ However, a flexible general practitioner of psychology could presumably have given the right kind of advice and “treatment” for as long as needed to achieve JMB’s desired state of “relaxed concentration” at the crease. He had been seriously interested in psychology since the mid-1960s, and so should have known how to sort the wheat from the chaff in choosing someone. As to what would then have been a residual, less severe, tendency to “open-up” against pace, the need was for an on-going relationship with an adviser he could put his faith in – as pointed out in the biography. There were a number of candidates available.

There was also more than one way to skin this cat: as an alternative to the conventional keeping sideways to the bowler technique, there was the fully open-chested-to-the-bowler method favoured by Gary Sobers (shown, for instance, on the cover of his 1985 instructional book). Additionally, JMB could have worked on better judging which deliveries to let go by on length or width; like most Test batsmen, he could have safely resisted attempting to make contact on more occasions.

Had such help been obtained, there is not much doubt that JMB would have been able to put it into practice at the crease. He was a determined and conscientious character, and so would have worked assiduously to improve his mindset and technique. He was also agile on his feet, being a capable wicket-keeper. And he had the patience to build a big innings – indeed, on occasion he displayed a Boycottian desire for amassing runs – witness his score of 312 when opening for MCC’s Under 25 team in Pakistan against North Zone in February 1967; and his 202 (made in 361 minutes) when opening for the MCC in India against West Zone in November 1976.

Given this, and JMB’s cogent reasoning for his own poor Test record with the bat, I would have expected Peel to subject the negative view he formed of JMB’s unexploited potential to the kind of straightforward, common sense, tests that I have been driven to make – as now outlined.

The principal test of what JMB was capable of – with a corrected mindset and sounder defence against pace – is to determine what his Test average would have been if his high frequency of dismissal before having played himself in is normalised, instead of accounting for 65% of his Test innings. Taking completed innings of below 20 runs as the marker, the norm is established in relation to 14 batsmen who usually, or quite often, either opened or went in at first wicket down for England during the decade 1974-83 (minimum of ten Test matches). These 14 batsmen combined were dismissed for under 20 runs in 48% of their innings during this period. Applied to JMB’s average for his dismissals under 20 (at 8.1 runs) and applying the balance of 52% to his actual average for his 20 plus innings (at 52.1) yields an adjusted overall average for him of 30.1. If JMB were in the middle of the top half of these 14 comparators, his adjusted average would then be 33.9.

As a supplementary test, I looked at what the typical relationship is between Test and county averages (over a whole career) for those who usually batted in the top seven in the order for England during the 1974-83 decade (minimum of 10 Tests). After setting aside those six players with a “perverse” ratio (Test average higher than their county average), the representative ratio of Test to county average for the 18 players comes out at 86.4% (within an overall range of 64-97%). This implies a potential Test average for JMB of 33.1; and if he were in the middle of the higher half it implies a Test average for him of 36.2.⁹

Hence, on these two bases it is reasonable to expect results for JMB with the bat in Tests to have averaged out in the early to mid-30s – an uplift of some 30-50% on his recorded average. Placing his potential in this range, under a corrected back foot defence scenario against pace, also seems plausible intuitively. As an opener, being the position he was most suited to in temperament and approach,10 JMB would have migrated from the likes (during his era) of Bill Athey, Wayne Larkins and Barry Wood, to join the ranks of Graham Fowler, Brian Luckhurst, Chris Tavaré and Bob Woolmer. It would likely have come with an aspiration to emulate Middlesex and England’s John Edrich, a batsman with whom he had some similarities in manner of playing.

This conclusion chimes with JMB’s own statement, quoted earlier – thinking that he might, on a re-run of opportunities, now be better able with his learnings to do moderately well in Tests with the bat rather than poorly. This is not to say that Peel’s assessment is necessarily “wrong”. Rather, to suggest that a contrasting conclusion can be made out and defended against objection – in short, tenable.

Finally, why has JMB been so concerned for such a long while after finishing his cricket career about not doing more to exploit his potential as a Test batsman and, especially, why so strong with self-criticism in public – in published material in various places – rather than only in private? This is intriguing. My personal speculation is that he would, justifiably, have harboured a conviction early on – during his undergraduate days at Cambridge – that he could succeed at Test level with the bat. His own reasonable hopes were shared by some others, including no doubt his father, Horace, to whom JMB was close – a capable sportsman who reached first class level at cricket with Yorkshire and Middlesex, and played club cricket successfully until well into his fifties. And who knows, maybe subconsciously (on the other side of the ledger) trying to live up to the deeds of his namesake, Walter Brearley, who did so well as a fast bowler in his three Tests for England against Australia in 1905 and ’09. Hence, a strong and lingering disappointment, lamenting what could have been.

Actually going public with his self-reproaches may, I feel, have acted as a liberating catharsis – a release, and thereby relief, from the trauma, disappointment and regret experienced – perhaps heightened by introspection that tends to come with a subsequent career in psychoanalysis. A fair amount of material in his two recent books can, I surmise, be viewed this way.

To end with a general comment on biographies of sports people: they are more valuable when, like this one, they are thought-provoking and motivate further enquiry – pursuit of the issues raised. Before opening this one by Peel, I had only general impressions of Mike Brearley the cricketer.

Tempus in agrorum cultu consumere dulce est (Ovid, 43 BC-18 AD).11

¹ Postscript to Phoenix from the Ashes, being JMB’s account of that 1981 series. Hodder and Stoughton, 1982.

² JMB displays one-sixth less variance than the batsman statistically closest to himself, and nearly two-fifths less variance than the eight comparators collectively. They are: John Edrich, Brian Luckhurst, Chris Tavaré, Dennis Amiss, Geoff Boycott, Graham Gooch, Chris Broad and Tim Robinson.

³ The notable overseas bowlers being: Sarfraz Nawaz, Bishan Bedi, Vanburn Holder, Srinivas Venkataraghavan, Andy Roberts, Richard Hadlee, Dilip Doshi, and the South Africans Clive Rice, Garth Le Roux and Mike Proctor. The notable England ones being: JK Lever, Underwood, Willis and Hendrick.

4 The others being Wood, Close, Edrich, Woolmer and Steele.

5 M.C.C. The Autobiography of a Cricketer, 1976 – see Chapters 5-8.

6 The corresponding figure during JMB’s seasons as an under-graduate at Cambridge (1961-64) was considerably lower, at 13% (4 of 31 such occasions) – perhaps a reflection of the abnormally batsmen-friendly pitches when playing at home. For his relatively few matches for Middlesex during this period, the figure is 23% (3 of 13).

7 favours the brave.

8 indicated by The International Society of Sport Psychology becoming a prominent organisation only after a world congress on the topic in 1974. Professional golfers, for instance, didn’t benefit in any numbers until the late-1970s.

9 Perversity is probably due to being inspired by the big stage with county matches tending to become something of a chore over a lengthy career.

10 And having a slightly higher average opening in Tests than batting lower in the order.

11 It is delightful to spend one’s time in the tillage of the fields.

Peter Kettle was born in London but has lived and worked in Melbourne for more than 30 years. He has written a number of books including two that we have featured. Rescuing Don Bradman From Splendid Isolation was reviewed by Martin here, and by Dave here. Both also reviewed his play A Plea For Qualitative Justice, Martin here and Dave here. Peter has also written a biography of the Leicestershire and England batsman of the 1920s and 1930s, Eddie Dawson.

Leave a comment