Jessop’s Son

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 48

Author: Battersby, David

Publisher: Battersby, David

Rating: 4 stars

A new decade dawns with the twelfth instalment in what David Battersby describes as an occasional series of booklets. Spread over four years that strikes me as a bit of a misnomer, given that in addition to an annual average of three booklets a year he has also self-published a biography of William Woof, and a book about the early years of Gilbert Jessop Snr. So perhaps in truth it is a regular series rather than an occasional one, but either way Jessop’s Son is the best so far, so I hope there are plenty more titles in the offing.

On the basis there might be a few who have stumbled across this review who are not familiar with the background Jessop Snr was one of the great names of the ‘Golden Age’. He was a hard hitting batsman who scored a famous matchwinning Ashes century in 1902, a genuinely fast bowler and, in an age where fielding ability was nothing like so highly prized as today, one of the best fielders in the game. If his overall record in his 18 Tests does not indicate greatness his First Class record is rather better, and he was certainly a crowd pleaser.

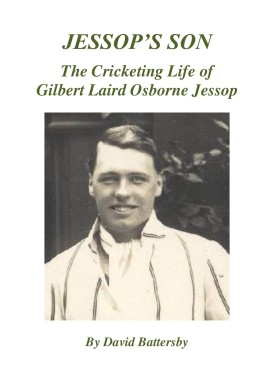

Jessop Jnr, an only child, was born in 1906 and appeared four times in First Class cricket. An all-rounder like his father he was another aggressive and fast scoring batsmen, albeit the son bowled off breaks rather than, like his father, as quickly as he could. Like the father the son went up to Cambridge, but there the career paths diverged as Jessop Jnr became a man of the cloth, ordained in 1931. Later on he was, for a time, a missionary. Jessop Jnr married fairly late in life, in 1974 to Pat, more than thirty years his junior.

As with most writing the quality of a finished product depends upon the material with which an author has to work. With the Jessop family Battersby already knew that what he sought did exist. Jessop Jnr had made family scrapbooks and photographs available to his father’s biographer, Gerald Brodribb, back in the 1970s. Fortunately, the age difference between Jessop Jnr and his wife meant that his widow is still with us. A Gloucestershire historian pointed Battersby in the direction of the surviving Jessops and once more they opened up the family archive and, albeit with a different emphasis, Battersby was able to make extensive use of that the same way as Brodribb had done almost half a century before.

As he always does for his historical writings Battersby has also trawled carefully through the British Newspaper Archive, and in doing so has gathered up many contemporary reports of the Minor County and club matches in which Jessop Jnr played a starring role. Combining that research with the family heirlooms to which he had access results in an impressive booklet the family photographs, of which there are many, being particularly valuable.

The account of the life of Jessop Jnr that Battersby provides is a detailed one, particularly in relation to those cricket reports, and the booklet is a chunky 48 pages. It might have been better had it been a little larger still as the the use of a larger font would certainly have made the reading of it a little easier for those of us whose eyesight is not quite what it was in our youth. That said overall the appearance of Jessop’s Son is easy on the eye and, as indicated, the photographs which are of so much interest are very well reproduced.

Like Jessop Snr this reviewer was also inconsiderate enough to insist on naming his first born after himself, something which in mine and my son’s experience causes more problems than anything else. In this review, after much thought, I have decided that the ‘least worst’ way of distinguishing the pair is to refer to them as Snr and Jnr. Battersby uses ‘GLJ’ and ‘GLO’, which has a certain appeal but, ultimately I did at times find it meant I had to do a double take. That isn’t Battersby’s fault however, and is the one thing we can certainly hold against Gilbert Laird Jessop of Gloucestershire and England. I was also stopped in my tracks by a couple of what I will describe as ‘continuity errors’. When books from professional publishing houses contain factual mistakes it is certainly irritating, but with private publishers, whose organisations do not extend beyond them and their nearest and dearest I have to say I find the occasional slip, as here, rather more endearing than annoying.

The bad news is that although Jessop’s Son appears in a seemingly not unreasonably limited edition of 115 copies Battersby, having by now garnered something of a reputation has, with the benefit of a little advance publicity, already sold almost all of thosecopies so anyone interested had best get in touch fast – as ever for those interested in the booklet Battersby can be contacted by email at dave@talbot.force9.co.uk

Leave a comment