Stories of Cricket’s Finest Painting

Martin Chandler |Published: 2019

Pages: 288

Author: Rice, Jonathan

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 3.5 stars

Pitch have been around for more than a decade now, and have produced some excellent cricket books over that time. Some of the best have been biographical in nature, dealing with famous men like Tony Greig, Barry Richards and Colin Cowdrey. But Pitch are perhaps most notable for having pushed into new areas such as the rise of Afghan cricket, cricket around the world and the 2015 Women’s Ashes.

Purely historical works, which I will concede immediately have a more restricted market, seem not to have been Pitch’s priority, although in saying that there have been excellent biographies of Albert Trott and Percy Jeeves. I was therefore particularly pleased to see this one, centred around a single County Championship match that was played in 1906, even if it was a match in which my beloved Lancashire picked up a fearful hammering.

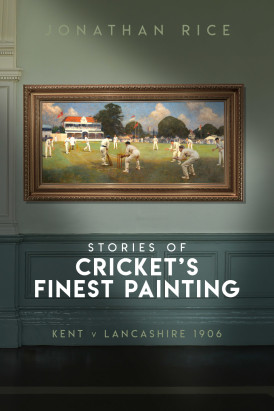

The centrepiece of the dust jacket is a small scale representation of one of the most famous cricketing paintings. It was commissioned by the long time Kent president and cricketing grandee Lord Harris. The reason for this was to celebrate Kent’s first County Championship success in 1906, and the match chosen the home match against Lancashire played during the Canterbury Festival. The original painting measures 7’6” by 3’9’’ and, seen in its full glory, is a hugely impressive piece of work.

The old festival itself continues to this day, making it the longest running in the game. The first part of the book is a history of the festival and of the famous St Lawrence ground at Canterbury. From there the narrative moves on to the artist, Albert Chevallier Tayler, a famous man and remembered today amongst cricket memorabilia collectors thanks to his The Empire’s Cricketers, a 1905 published large format book containing 48 chromolithographic plates of the game’s foremost exponents.

From the subject of the artist author Jonathan Rice goes on to take a look at the state of the nation, and indeed the wider world, in 1906. The contrast between the austere Victorian era and the considerably more relaxed Edwardian decade is an interesting one, and that social history is augmented by a detailed look at the state of the game of cricket in 1906 and how the, for Men of Kent and Kentish Men, season of triumph unfolded. Inevitably and entirely properly there is then an account of the match itself, albeit one that will cause some pain to Lancastrians. Kent won by an innings and 195 runs courtesy of the batting of three amateurs (Kenneth Hutchings, Jack Mason and ‘Pinky’ Burnup) with a little help from one professional (James Seymour). Lancashire were bowled out twice by a combination two paid bowlers; the great slow left armer ‘Charlie’ Blythe, and paceman Arthur Fielder. None of the Lancastrians had much reward to take back to Manchester with them.

The largest part of the book is taken up with pen portraits of the men who Chevallier Tayler painted. All of the Kent side are portrayed and the Lancashire batsman whose backside features in the foreground is the legendary JT Tyldesley. Also portrayed is the non-striker, and this is Billy Findlay, a man who had played for Lancashire in the past but who played no part in the 1906 fixture. The reason for Findlay becoming the non-striker seems to have been as prosaic as him, having moved down south, being available to ‘sit’ for Chevallier Tayler. The final essay is on the umpire at the bowler’s end, Alfred Atfield and, although he does not appear in the painting Rice does go on to tell his reader a little about Valentine Titchmarsh, who was stood at square leg.

The players’ life stories take up about a third of the book and deal with their entire lives, thus the chapter entitled What Happened Next is fairly limited in scope. In it Rice goes on to deal with the rest of Lord Harris’ long life, before looking at what became of Chevallier Tayler and, naturally, of his famous painting. In the art world Chevallier Tayler continued to be successful, but his life was stalked by tragedy and he died at aged 63. His painting was, despite its undoubted quality, never the commercial success it was hoped it would be. Nonetheless the original increased greatly in value and, in the early part of this century, Kent decided to commission a copyist to produce a replica and to sell the original. The copy is still hung in the Pavilion at Canterbury and the original, thanks to the charity that paid a record £600,000 at Sotheby’s in 2006, is on display at Lord’s.

And there Stories of Cricket’s Finest Painting might well have concluded, but in fact Rice adds a lengthy digression; Cricket Then and Now. As the title suggests it is an examination of changes in the game over the last 113 years and, the subject I least expected to read about makes an appearance as Rice looks at the development vexing many at the moment, next year’s English franchise competition, the much maligned Hundred. In forty or so pages there is much food for thought.

Stories of Cricket’s Finest Painting was an excellent idea. It is well written and attractively presented. For those who remain under the spell of the ‘Golden Age’ it is highly recommended.

Leave a comment