A Sort of Homecoming

Martin Chandler |Published: 2018

Pages: 461

Author: Blewitt, Paul

Publisher: Straccotto Books

Rating: 3.5 stars

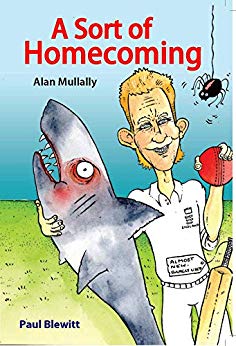

Don’t judge a book by its cover is an instruction I have been issued with many times although, perhaps unsurprisingly, rarely in the context of an actual book. It is a particularly apposite idiom in the case of A Sort of Homecoming however, not so much because there is anything wrong with its cover, but more because it creates the wrong impression. Examples of artist Rob Wilkinson’s humorous caricatures crop up from time to time throughout the book, and are entertaining and worthwhile, but seeing one on the cover meant my initial impression was that I was going to read something akin to those rather tedious books of cricketing humour that appeared in the names of a number of Australian Test stars from the 1970s.

In reality I immediately found out that the book is in fact what it describes itself as, which is a first person biography. I am not entirely clear how that differs from a ghosted autobiography. It is arguably a distinction without a difference, but if there is a difference perhaps it is simply that Alan Mullally and Paul Blewitt are old friends, rather than just a writer and a sportsman thrown together at the behest of a publisher.

Which brings me on to Alan Mullally, an English born, Australian raised left arm pace bowler. Between 1996 and 2001 Mullally appeared in 19 Tests for England in which he took 58 wickets at 31.24. It wasn’t the most successful time for English cricket, and he never ran through the opposition, but those numbers are respectable enough. In ODIs, the only shorter format there was in Mullally’s time, he was picked 50 times over the same period. He made rather more impact in the fifty over game, and has a good record both in terms of economy and strike rate.

As with so many sportsmen’s biographies and autobiographies of recent years A Sort of Homecoming does not start at the beginning of its subject’s story. The book starts with the end of Mullally’s cricket career, and the decision to retire that he took at the beginning of his benefit season of 2005. It is an impressively honest portrayal of the feelings of a man who knew he had got to the end of the road, and sets the tone for the rest of the book.

After the hard hitting introduction Blewitt’s reader does get the story of Mullally’s family, a childhood in Australia, and the trip to the top of the game that followed. The account is not just one of what happened and a series of bland match reports. The narrative deals fully with Mullally’s feelings through the highs and lows of his career, and his private life, as well as dealing with his thoughts about his fellow cricketers. He clearly wasn’t too keen on Dominic Cork and Kevin Pietersen, but that pair apart gives a generally positive impression of those he played with and against. Many of the passages in the book involve Mullally opening up over his thoughts, none more so than in respect of his friendship with Adam Hollioake, and his feelings when Hollioake’s younger brother Ben was tragically killed in 2002.

Life was, to say the least, unkind to Mullally after he retired from the game. The story of a failing marriage will strike a chord with any man who has spent time kidding himself his relationship would be alright in the end, only to be left with painful feelings of betrayal and emptiness after discovering his wife’s infidelity. To compound that Mullally was subsequently badly let down by a friend who helped pick him up after the divorce, and then persuaded him to put that capital his former wife left him with after the divorce into a scheme that produced no return for Mullally, and ended up in bitter recriminations and the investor losing his savings. The death of Mullally’s beloved father then pushed him over the edge and he started to drink too much. In 2016 Mullally ended up in court on a drink driving charge, way over the legal limit and crashing his mum’s car.

So Alan Mullally is yet another sportsman who has tasted success at the highest level yet not found life at the top to be all plain sailing in the way that we ordinary recreational players fondly believe should always be the case. At times Blewitt’s frankness, which can only have come from Mullally himself, is quite disarming but the result is that by the time the reader gets to the last of the sixty chapters of A Sort of Homecoming he or she will have developed considerable sympathy for ‘Spider’ Mullally, and the fact the book ends on an upbeat note is something of a relief.

By virtue of being a human story as much as a cricketing one the absence of any sort of statistical appendix is not as much of a problem as it sometimes is in books of this nature, nor the lack of an index, although this reviewer would still like to have seen both. The number of and quality of the reproduction of the photographs in the book leaves a little to be desired as well, but at the end of the day the book is, effectively, self-published and I dare say that something this size, were it to contain a dozen or so pages of full colour images printed on art paper, would have cost considerably more than the £12.99 the book retails at. In any event if you want to see the photographs in full colour there is always the publisher’s website and, I suspect, the ebook as well. All in all A Sort of Homecoming is an engrossing and thought provoking read, and certainly recommended.

Leave a comment