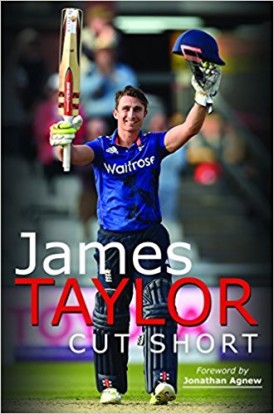

Cut Short

Martin Chandler |Published: 2018

Pages: 185

Author: Taylor, James

Publisher: White Owl

Rating: 4.5 stars

I would have liked to be able to have a moan about Cut Short, the autobiography of James Taylor. I would like to be making a point I have made before, about the absurdity of the concept of a 28 year old cricketer writing an autobiography whilst subject to the constraints of a central contract. Such books generally sell reasonably well, and generally contain a few points of interest, but they usually pose at least as many questions as they answer, and are never entirely satisfying.

In the case of James Taylor, sadly, the usual rules do not apply. His career was over at 26, cruelly ended by a diagnosis of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. He and I would both prefer it if he had grown into the stylish Test match batsman he always threatened to become, but the fact that he wasn’t able to do so makes for a compelling and, in a number of ways disturbing story.

Before James Taylor’s diagnosis I had, like most people, never heard of ARVC. Health issues are ones that, like many men of my age, I have always found difficult to face. I take the view that because I neither drink nor smoke, get a reasonable amount of exercise and eat the right food (albeit a little too much of it at times) that I am doing okay. What I would rather not hear about is how a man half my age and a finely tuned athlete suddenly has his future changed beyond recognition by a latent health problem that has lain undiagnosed for years.

When the news first broke about Taylor’s retirement I started to read a few articles about what had happened to him. I suppose I always knew that, in truth, the swiftness and permanence of the announcement must be all the evidence needed as to the severity of the problem. But then I saw Taylor doing a stint at punditry. He looked to be in good health, did not seem unhappy, and for a bloke wholly unused to sitting in a studio talking about cricket, he seemed to be pretty good at it. At that point I am ashamed to say I didn’t give the subject of Taylor’s health any further thought.

And then I read Cut Short. I now know that Taylor’s life was and, to a large extent remains, on the line. The observation that most diagnoses of ARVC are made post mortem is a sobering one. I have an understanding now of how difficult those first few weeks were, that even now Taylor is not ‘well’ and that whatever impression his calm exterior might suggest, life for him is never going to be ‘normal’ again, and why in the future it won’t be his bat doing the talking.

Much of Cut Short is concerned with more important things than sport, but it is still a cricket book and contains a cricketer’s story. Accounts of cricketers’ lives always benefit from the inclusion of a few statistics, and Taylor’s are more interesting than most. His batting average in the handful of Tests in which he was able to play is modest, but in ODIs, T20, List A and First Class cricket his achievements are impressive and, given another half a dozen years, it is surely inevitable that he would have ended up with a Test batting average well above forty.

One thing Cut Short lacks is an index, an omission I usually find frustrating, but which I think on this occasion can probably be justified. With such a facility I think many readers might easily start in the wrong place, doing what I tried to do, and immediately look up the name ‘Pietersen’. Of course Taylor’s impressions of the mighty KP, with whom he shared that stand of 147 on debut, are important, but hardly in the same league as a matter of life and death.

For those who cannot recall exactly what KP has said about Taylor that is, of course, reprised and the reader does get Taylor’s take on what occurred and his opinion of KP. There is nothing here that will take anyone by surprise. What Pietersen is really like is a subject that has been discussed by many of his peers, with very little disagreement between them. As Taylor wistfully observes ‘never meet your heroes’ is one of life’s great truisms.

Cut Short is not the first outstanding human story cricket has produced in recent years, but its subject matter is certainly unique. It also contains some interesting passages on the game in England in the early part of this decade and, just to throw another genre into the mix, towards the end there is a bit of romance as Taylor contributes a chapter on his wife Jose, and she one on him.

The final chapter of the book is simply called ‘Now’. By this stage the reader already knows what makes James Taylor tick, but it is an evocative summary that, as much as anything, showcases the skills of ‘collaborator’John Woodhouse, a man who has already helped Graeme Fowler and Steve Harmison put into print exactly what they wanted to say.

Cut Short is going to pick up a number of awards next year and deservedly so. It is highly recommended.

Leave a comment