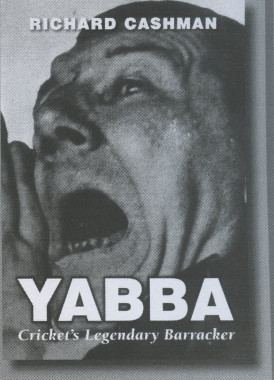

Yabba

Martin Chandler |Published: 2015

Pages: 96

Author: Cashman, Richard

Publisher: Walla Walla Press

Rating: 3.5 stars

Most cricket lovers with an interest in the inter-war period will recognise the name Yabba or, to give him his proper name, Stephen Gascoigne. His reputation was gained as a barracker, whose stentorian tones and ready wit were part of the entertainment at the SCG for many years. His fame reached its height during the 1932/33 and 1936/37 Ashes series during which he lent his name to newspaper columns.

Cashman is the first to admit that his book cannot be considered a biography in the fullest sense of the word, simply by virtue of the paucity of information available about Yabba’s early life. Some of what Cashman does know, such as the fact Yabba served in the British Army in the Boer War at the turn of the century, asks more questions than it answers. That much conceded overall Cashman does an excellent job of painting a picture of Yabba’s life and times given the limited material at his disposal.

Crucial to Cashman’s purpose is to explain just what barracking was. I use the past sense because in terms of the way Yabba and a legion of contemporaries behaved the concept simply doesn’t exist anymore, and on English cricket grounds it never has. It certainly isn’t sledging, and despite being partisan is not as many might imagine. But at least I understand exactly where Cashman is coming from because, just once, I did have the pleasure of experiencing barracking first hand.

Back in the late 1970s, for a few years, I used to go to the occasional Rugby League game. My local team, and the one I chose to follow, was Blackpool Borough. The club no longer exists, and is not greatly missed. It was never well supported, and enjoyed little success. In fact it would be fair to say that for almost the entire duration of their existence Borough were the League’s whipping boys.

After the Rugby League was split into two divisions in the early 1970s Borough Park rarely played host to the big teams, but one year (it was four up four down between the divisions) one of the game’s major draws did slip up and find themselves in the second division. It was a thoroughly dank and dismal Borough Park the afternoon the big boys came. Despite the inevitable drubbing I expected to follow, I still thought it would be an experience to visit Borough Park populated by more than the usual couple of hundred hardy souls who normally dotted themselves around the stadium.

These were the days when British football grounds, where I went for my live sport much more often than Borough Park, were scarred by regular outbursts of violence between rival supporters and a heavy police presence at games was the norm. It was never the same in Rugby League, but I still found it a little disconcerting when, about ten minutes before kick off, hundreds of opposition supporters poured into the ground and decided to take up residence around the spot which by now my mate Des and I viewed as our own.

They were a noisy lot, and they had plenty to say to the few of us sporting orange scarves, and clearly had a low opinion of our team. That at least was something we had in common, although after seriously contemplating moving on we decided to see just how nasty these boys from across the Pennines were. The catalyst for our decision to stay started with the comment; fookin’ Borough, they’d struggle to beat a side raised from t’ local nurses home. Des came up with the rather clever response; I don’t like to disappoint thee lad but we lost to them midweek. An uncomfortable split second’s silence was followed by a wave of laughter and the complete disappearance of any tension.

Once the game started the banter stopped for a few minutes whilst our guests got to grips with the unexpected as the match turned out to be a remarkably even one. Inspired no doubt by the big crowd our lads raised their game to heights we had not dreamed possible, and it was only in the dying minutes of the contest that the Borough finally fell behind. For most of the preceding eighty minutes those around us had flung a good deal of stick at their own players, and offered plenty of advice. Most of it was amusing, and some downright hilarious. At the same time they had been generous to a fault in their reaction to the quality of the Borough’s play. Remarkably there was virtually no swearing – Granny might not have approved of some of what was said, but she certainly wouldn’t have been offended.

The referee came in for some of the worst treatment, and to be fair it wasn’t his best game, and I was to see something else I had never seen before. At one point a lad right in front of me questioned the official’s parentage in colourful terms. It was one of those occasional moments at a sporting event where everyone else seemed to pause to draw breath simultaneously, so the cry was heard loud and clear across the whole ground. The referee turned to face his tormentor and walked towards him, finger wagging and eyes bulging; I heard that young Ned Cowperthwaite, and ah’ll be telling thy mother about tha’ wicked tongue on Monday. I was glad he knew the offender’s name – at least I could be confident he didn’t think it was me.

The barracking that day certainly added an extra dimension to my enjoyment of proceedings, and I fully understand why Yabba and his like had exactly the same effect at cricket grounds. Cashman’s analysis and description of the times is revealing, the stories entertaining and the size of Yabba’s reputation much more readily understood at the end of the book than at the beginning.

Yabba is not necessarily a cheap read, but is certainly an interesting one. The paperback version, limited to 200 signed copies is a relatively modest 35 Australian Dollars rising to 130 Dollars for the hardback run, 70 copies and signed by Yabba’s granddaughter, the sculptor who produced the bronze that graces the site of the old ‘Hill’ at the SCG and the Chairman of the ground’s trust as well as the author.

Leave a comment